© Meg Dillon 2008

Australian Colonial History

Chapter 4

More arduous than being a soldier? Convict police — their work, leadership and

the stresses of the job

This chapter will use the Campbell Town bench book to explore the realities of police work in the mid 1830s. While previous historians have catalogued

many incidents of common police corruption, mostly compiled from newspaper reports, there is a danger that the emphasis of the existing literature will

leave the impression that the force was ineffective. As Sturma points out, there is a second danger too. Police corruption has historically been a long run

phenomenon and is certainly not limited to the era of convict policing.

1

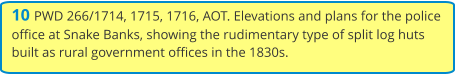

This chapter will attempt to rectify the deficiency in the current literature by employing the magistrates’ bench records to explore the day to day realities

of convict policing in the 1830s, as the duties of the police magistrate and his staff expanded during the period of Arthur’s administration. The court

records provide a means of exploring the ways convict constables reacted to issues of loyalty, the power and class struggles with local magistrates and

abuses from other convicts and emancipists. This chapter will approach the convict constables as people caught for a moment in the public gaze, and

demonstrate why the job of policing a district was seen by some of their contemporaries as a more arduous job than soldiering.

2

While the variety of police work had increased by the mid 1830s, putting pressure on both superior officers and constables, the quality of active policing

was still in its infancy. Although Arthur argued their role was “detecting” as well as control, there were few examples of successful detecting in the 1835

bench book.

3

Such work was often left to the senior officers if it was done at all. John Lyall was the acting chief district constable when Henry Emmett, a

local storekeeper, called him in to investigate a suspected theft at his store. It must have surprised Lyall considerably to discover that Emmett had almost

completed the entire investigation before he arrived. Indeed Emmett later used the court as a stage to play out his powers of deduction almost as if

suggest that the local police and their commanding officer were far less capable than he in resolving cunning thefts. Emmett delivered a masterly

summary of his efforts to the court, which contained more than a hint of irony. He charged two of his assigned shop men with stealing 26 gallons of

porter, 13 gallons of Cape wine and 4 gallons of rum over a period of several weeks. The quantity was too large for two men to consume without Emmett

noticing they were frequently drunk, so it was probable they had stolen the liquor to resell it illegally around the village.

When he discovered his loss, Emmett removed the assigned servant, who had been ordered to sleep in the storeroom to protect the goods, and had

another convict securely nail up the loft floor above the shop. He returned secretly, late on the Saturday night, and placed some goods on top of the

liquor casks. On Monday morning he found the goods had been moved. In addition, he explained to the court, “I felt assured the premises had been

entered and proceeded to examine the boards (of the loft floor)…I immediately perceived one of the boards to be split, by which means it was moveable

at one end, and by moving it found a considerable opening was made to the cow house below”.

Certain that he knew who the thieves were, Emmett sent for chief constable Lyall, who arrived and searched the servants’ rooms, where he found several

bottles of spirits. Although this appeared to be proof enough of their guilt, Emmett told the court that he continued to gather evidence. “I afterwards

examined some of the spirit casks, in particular a cask of rum, which had been deposited with the store on Saturday last only and found that something

more than two gallons had been taken out of it. From a cask of brandy I also found something more than one gallon had been taken. I have compared the

rum in the bottle produced by Mr Lyall with a sample of that taken by me from a cask in the store, and I have no doubt it is the same rum. I have not yet

compared the brandy”.

4

Emmett had suspected a long standing and continuing robbery, taken steps to prevent any further thefts, collected evidence of the break in, questioned

the suspects, noted their responses, and finally called in the chief district constable.

5

Emmett’s investigation was more detailed than any police

investigation that was recorded in the magistrate’s bench book for 1835 and implied that the concept of logical investigation was possible in 1835, but

more likely to be undertaken by the victim of a criminal act rather than the police or their officers. The truth was that in a rural police office the general

round of duties left little time for sleuthing despite the governor’s assertion that detecting crimes was one of the main duties of his police.

Rural police magistrates gained more responsibilities as their office began to function as the key local bureaucracy responsible for a range of duties that

later would fall under the jurisdiction of local government. Convict control remained a substantial part of the duty of constables, particularly the newly

recruited. They performed escort duties, attended to fines, dealt with disorderly persons, and enforced the growing numbers of regulations about

hawkers, carriers, bakers, coaches and permits for selling wine and spirits.

6

But the convict police were the magistrates’ deployable staff and had to

gradually extend their duties from these tasks to many additional functions. The increase in their duties sometimes perplexed their critics, who thought

that the primary function of the police was to exercise control over the district’s convict work force and not to interfere with the likes of free settlers.

By the mid to late 1830s, police magistrates were responsible for supervising the work of district surgeons, rural postmasters and their paid convict post

messengers, local coroners and inspectors of stock. They also made recommendations to these appointments thereby exercising a degree of local

patronage.

7

They enforced the licensing laws and prosecuted local publicans for harboring and serving convicts.

They established pounds and deployed constables to run these, an unpopular duty, as farmers resented paying fines for stock that had strayed and hated

the Slaughtering Act which forced them to pay for inspectors who verified the ownership of all stock slaughtered for meat. The magistrates oversaw the

local Courts of Request that settled small debts thus creating security in everyday commercial transactions. The magistrate’s office sometimes dealt with

welfare issues concerning women and children. Frederick Forth, police magistrate in 1836, for example, received a letter from his district constable at

Ross asking what could be done to help a married free woman who had been turned out of doors with a black eye by her husband who had been drunk

for a week.

8

The magistrate’s office also acted as a labour exchange responding to desperate settlers seeking convict labour for the grain harvest.

9

The

office provided information about the availability of ticket of leave men, taken from the monthly musters, and sometimes public works convicts could be

temporarily deployed to assist settlers to get their crops in.

In addition, some police magistrates could be expected to supervise and assist extensive public works projects in their areas. Throughout the early 1830s

the various police magistrates in the Campbell Town district supervised the expansion and repair of police buildings in the government compounds and

at remote police outposts.

10

Superintendents of road parties in the district were supported by local police who helped move convict gangs and

equipment to new sites, and new levels of co-operation were initiated between the Roads and Bridges Department in Hobart and local police magistrates,

including the use of shared offices for police and road project superintendents.

11

In 1836, police magistrate Forth, a former military engineer, also acted

as superintendent of the public works gangs that built the Red Bridge in Campbell Town.

12

To cap things off, the role of keeping track of convicts also became more complex as increasing numbers of forms were required by the Chief Magistrate’s

Office and larger numbers of assigned and ticket of leave convicts came to work in the district. Annual convict musters, monthly ticket of leave musters,

abstracts of local absconders, weekly abstracts of cases heard, depositions for particular cases, police characters (references for convicts), travel passes,

financial accounts and pay abstracts were just a few of the dozens of documents that were produced or submitted to Hobart from the police magistrates’

offices.

13

Preventative policing also started to gain momentum by the late 1830s and some thorough police campaigns were mounted in the Campbell

Town district. For example, an extensive sweep through bush land was conducted by police, to burn temporary huts where absconders could shelter.

14

On another occasion, over forty men, including police, participated in a search for a bushranger, a costly exercise that ran over many days.

15

In an era of mounting demands the high turnover of convict police and their officers, who rarely stayed for more than three years in a rural police office,

presented considerable problems. While officers had high expectations of the constables’ performance of their duties, there were no plans to train them

beyond the imposition of a rigid system of military-style discipline.

16

The arduous demands of these duties were described by James Mortlock, who

served as a rookie constable for several weeks before persuading the police magistrate to transfer him to the less strenuous position of watch house

keeper. As Mortlock described it:

A petty constable being supposed continuously to patrol an appointed beat, from eight o’clock in the evening until six next morning, anyone thinly clad

found the duty very severe, especially in a strange place, during a dark, wet, cold night, the latter part of which he passed in a state of shivering, hungry

drowsiness, quite incompatible with effectiveness. The hours of darkness should always be divided into at least two watches. Those few weeks were

extremely harassing; I cannot remember that any period ever inflicted so painful a trial upon my fortitude…

17

The absence of active policing in preventing petty crime was seen by some contemporary critics and later historians as evidence of a widespread

corruption. While this was likely in some cases, the lack of preventative policing can also be interpreted as a lack of active leadership by local superior

officers as well as a failure to develop policing procedures that actively investigated local crime. At this time, however, neither the new British police

services nor the colonial forces had reached a stage of development, when leadership or policy goals could be clearly defined and implemented across

the force.

18

In Campbell Town, a heavy turnover of senior staff occurred between 1832 and 1836. The men who acted as police magistrate during those years were

local farmers, with business responsibilities, and each seemed to attract a level of local support from different factions. Simpson and Leake appeared to

be remembered fondly by local emancipists as fair men. On the other hand, some of justices of the peace criticized Leake for preferring the testimony of

convicts to the word of a gentleman. Leake’s replacement, John Whitefoord, was a farmer from Oatlands, who sustained strong criticism in local papers

from the emancipist and small trader factions, but was later appointed by Arthur to the permanent position of police magistrate at Oatlands.

Captain Frederick Forth, a military engineer, followed him to build the Red Bridge at Campbell Town and impose firm order. Forth had served on

Governor Arthur’s staff and was a professional colonial public servant who arrived from a position in the West Indies. Forth managed the bridge project

well, but was dismissed by Governor Franklin in 1839 for failing to adequately supervise the collection of quit rents in his office. His free clerk, George

Emmett, was at first charged with embezzling the funds but the charges were dropped when it was discovered the money was not missing but merely

mislaid.

19

There was a strong suspicion that as well as putting up a bond for the young Emmett, his friends may have also provided him with sufficient

funds to remedy the deficit and clear his name. His father and brother had been similarly charged and escaped prosecution while serving in other

government positions.

20

The quality and commitment of the local chief district constables in the mid 1830s was questionable too. There was little incentive for them to stay very

long in the job. Despite having the responsibility for the overall management of the local police force, their small salary of ₤75 per annum was generally

supplemented by holding other official part-time positions such as the summoning officer for the Court of Requests with remuneration of ₤50, pound

keeper or Inspector of Stock.

21

Some, like Francis Small only stayed ten months in the job before obtaining the better paid position of Superintendent of

Convict Writers in Hobart in February 1835.

22

Particular duties were unpopular with some convict constables. After the comforts and camaraderie of the police barracks at Campbell Town or Ross, the

isolation and loneliness of a month’s duty reporting to James Sutherland, the local magistrate on the Isis River was quite unwelcome. Sutherland imposed

strict control on the rostered constable who had to report to him daily and whose off duty hours were spent alone at the police hut situated on a

neighboring farm. An incident in 1835 demonstrated how severely Sutherland dealt with any perceived breach of duty. Sutherland explained to the police

magistrate how he was “called out of bed, by one of my servants, tapping very gently at my window, and telling me, that the constable was at that

moment, harboured in (Joseph) Albany's bedroom.” Sutherland left the house immediately and accompanied by his servant, William German, went out to

the kitchen door and confirmed that German’s information was correct.

William German had a busy evening. When constable Thomas Kirby arrived for the start of his month at the Isis, he first delivered the mail to Sutherland’s

where German had overheard the cook, Albany, arrange to meet Kirby later that evening. German went back several times to check the kitchen and cook’s

room to see what was happening and eventually around eleven o’clock, he heard somebody talking in Albany's bedroom. He went through the kitchen

and surprised the two men demanding to know: “What games do you call this. This I said in consequence of seeing meat and potatoes. Kirby asked me to

have some supper. I refused and went and told the men, in the hut and they advised me to tell my master.”

After informing Sutherland, German was keen to ensure that Kirby didn’t leave before Sutherland found him, “so I returned and held the kitchen door.

Kirby said Open the door—open the door. But I would not do so till my master came.” Sutherland was not convinced by Kirby’s explanation that he had

lost the key to his handcuffs and had returned from the police hut to try and find it, as he could have searched for it the next morning when he reported

for duty. Sutherland was scandalized that it was late at night and that “Albany was entertaining Kirby with supper.”

23

Convict constables had to be careful. There was always someone, either a settler or a fellow convict, who hated or mistrusted them and would try to

expose them to punishment. Police were caught between the two groups and in many respects could trust no-one. From the court records it’s not

possible to deduce whether German was trying to pay back either the cook or the constable, or even if he was one of those convict servants who had

aligned himself with his master’s interests and dobbed in fellow servants for his own gain. Kirby clearly knew he was not supposed to fraternize with

Sutherland’s assigned servants, when he tried to buy off German by inviting him to join them at supper. Whatever social contacts constables made with

the general convict class was likely to be viewed with suspicion by their officers as it could potentially compromise their loyalty.

24

The court records also

don’t include enough information to judge whether or not the magistrate suspected the friendship between Kirby and Albany was more intimate than a

simple social call, or more criminal, and that the two were involved with theft or fencing goods. Certainly the sentences given to both men suggest they

were being punished for more than having supper together. Albany was sentenced to thirty five lashes and returned to the Crown for reassignment and

Kirby was suspended and spent six months in a road party before resuming his police duties in Campbell Town. This harsh regime of isolation from both

the barracks and companionship throws some light on why another constable later in the year begged the chief constable to relieve him of his duty at

Sutherland’s.

25

There were other cases where convict servants tried to manipulate their master’s lack of trust of convict constables in the hope of gaining an advantage.

John Smith, a former baker, was employed as a convict javelin man (guard) at the Campbell Town jail. One morning after the church muster he came

across John Maker outside the Blue Anchor inn. Maker had worked for Henry Jellicoe, a local magistrate, for nine months and confided to Smith that he

wanted to leave Jellicoe’s employment and get another master. Smith told him that the way to do it was to pretend to abscond and that Smith could come

and pick him up at a pre-arranged spot. That way they could share the ₤2 reward that Smith would get for Maker’s recapture and Maker would be

returned to the Crown for reassignment. The plan was enacted, however, Maker was sentenced to Notman’s road gang instead of being returned for

reassignment as he had expected. A further unpleasant surprise was that Smith could not give him the ten shillings he promised until he got his quarterly

pay, but instead gave Maker tea and sugar to take with him to the gang. Six months later, Maker was released and assigned to another magistrate, John

Leake, at which point he pressed his claim for the ten shillings he was owed.

Maker not only wanted to get his own back on Smith, whom he believed had failed to honor their agreement, but felt he could use his new master to do

so. He told the whole story to Leake, including his recent attempts to collect the money owed to him. He confided that “about six weeks ago I was in

Campbell Town and I asked him (Smith) for money on account of the absconding. He gave me half a crown. This was at the back of the police office.”

Maker told Leake he couldn’t provide a witness to this conversation but when he asked Smith if that was all he was going to give him, Smith replied “Yes,

and if I was not contented he would give me in charge if I asked for any more”.

Although Leake claimed he was initially dubious of Maker’s motives, he was convinced when Maker explained that he didn’t tell Leake, “in order that the

javelin man might be prosecuted”, but that, “he thought it was a scandalous thing when he had bolted that the man should only pay him half a crown and

then threatened that if he troubled him for anything further he would take him into custody”. Apparently Maker’s sense of outrage moved Leake to take

action.

Leake advised Maker to make several applications in writing to Smith for the 7/6d that he owed him but Smith again refused to pay up, telling the man

who presented the order that he didn’t know Maker. Leake sent Maker back to Smith, with the groom accompanying him to act as a witness to their

conversation, but again Smith declined to pay up. However, Smith was becoming suspicious of Maker’s persistence and asked him how he came to serve

the order in that way and kept the note. The groom, when questioned later in court, was quite unhelpful to either party in the matter, saying he had only

seen the note passed to Smith but hadn’t heard what they spoke about.

Meanwhile Maker claimed he had met Smith later, while he was droving some sheep into the village and arranged to meet him near the jail where he

“gave me about a quarter of a pound of tea and about two lbs of sugar.” By all accounts, either Smith felt he had paid off Maker sufficiently with a half

crown and two lots of sugar and tea, which apparently he had taken from the jail’s supplies, or the tale was a fabrication.

26

The police magistrate

dismissed the case for lack of evidence thus avoiding antagonizing Leake, one of his local magistrates, while at the same time putting his convict

constable—Smith on notice. Making something on the side out of police work, if that was what Smith had actually tried to do, was a lot more difficult than

the critics of the police anticipated. Any disgruntled convict with an axe to grind could complain against them and at least get a hearing, apparently

without much risk to themselves even if they implicated themselves in an illegal transaction.

In any case, additional income from rewards for apprehending absconders or drunks was actually quite modest if other rural districts were similar to

Campbell Town. The local courts processed around 110 men for being drunk that year, which raised around ₤28 from the 5/- fines.

27

In addition,

constables apprehended around 36 absconders, so around ₤72 could be distributed from the ₤2 rewards. Twenty one constables claimed rewards, but

most only apprehended one or two absconders during the year. Three constables seemed more successful than most, although by October senior

officers were beginning to wonder if some constables were deliberately losing prisoners they were escorting in order to try and claim a reward for

recapturing them. Constables Holden and Moore each captured four absconders, but Moore was eventually fined for letting prisoners escape. William

Bowtell held the district record for capturing five absconders.

28

However, most of the Campbell Town constables would have been lucky to earn an

additional ₤2 - ₤3 from rewards and fines in 1835.

Yet even if it was difficult to make extra money out of police work, some police had information to exchange that they could use to their advantage. Stock

theft was rife in the district according to settlers, but few convicts or emancipists were prosecuted for it. As chief constable Lyall found out, they operated

at night and in out of the way places which made them too hard to catch in the act. Perhaps convict constables at Lake River or St Pauls Plains had

suspicions or even firm information about some local characters, if they did, they rarely appeared to follow it up.

However, this information could be a very valuable commodity of exchange for a convict constable in trouble. Constable Richard Collins, a former basket

maker from Woolwich, was only twenty four years old when he was sentenced to nine months with the Constitution Hill road party for inducing two

assigned men to buy him drinks at the Blue Anchor Inn in Campbell Town. He had an excellent conduct record and this was the first misconduct recorded

against his name in the six years since he had arrived in the colony.

29

Collins only stayed four weeks with the gang before absconding. Four soldiers later testified they overheard him say “he would rather hang twenty men to

save his punishment on a chain gang”, and although Collins denied using this phrase, it seems clear that his first experience with a road party created a

very strong incentive for him to avoid returning to his punishment.

30

Collins remained at large for eight days at the end of February, during which time

he made his way back to the Campbell Town district. There he gave himself up to Mr Davidson and Archibald McIntyre, the divisional constable, on

Davidson’s farm at Salt Pan Plains.

31

He appeared before Magistrate Whitefoord and was initially arraigned to be returned to the Constitution Hill road

gang for sentencing.

Collins spent ten days in the Campbell Town jail waiting to be returned to his gang, and during this time he and constable Thomas Griffiths devised a plan.

Collins told the police magistrate that he had valuable information that could convict sheep stealers at St Pauls Plains on the property of the magistrate,

Major William Gray. Eager to improve the local conviction rate, Whitefoord ordered Collins to work with Griffiths at the Avoca police office rather than

returning him to Constitution Hill.

A fortnight later, the two constables staked out the hut used by a couple of ticket-ofleave convicts named Macpherson and Spicer who worked for Gray.

Griffiths told the magistrate that early in the morning they saw “James Macpherson and another person killing a sheep which proved to be the property of

Major Gray”. As they moved in to arrest them, one escaped, but Macpherson was secured. They picked up a third man, James Spicer, in the hut. Several

days later, they apprehended William Duncan whom they strongly believed “to have been the person who was with Macpherson on the night in question.”

As Griffiths put it: “He answers to the description of Macpherson's companion in all respects. I can’t venture to swear to him—having had no knowledge of

the prisoner before, and the night being dark”.

Collins could do little better. Although he believed Duncan to be the culprit, he confessed that: “I can’t swear to him.” He reported, however, that he had

seen Duncan at Avoca, the night before the offence took place and had seen him several times at Macpherson’s hut. Griffiths further damned Duncan by

claiming that, “the prisoner has told me he is night shepherd to a person named Smith who bears a very indifferent character. He left the neighborhood

of Avoca directly the subject of sheep stealing was made public”. Duncan countered these claims by providing an alibi of sorts for the night. According to

his testimony he had stayed with Robert James and Paddy Sullivan at Avoca “from dark at night to sunrise” and volunteered that Sullivan at least had

been sober.

Given the fragility of the evidence, Police magistrate Whitefoord acted with caution. All three men had their tickets of leave suspended. Duncan was given

some benefit of the doubt. He was sent to the town surveyor’s gang in Launceston, one of the lighter punishment stations. The charge against Spicer was

dismissed as he had not been caught with the sheep. Nevertheless, he was relocated to a road party for twelve months.

Immediately, however, the case raised public suspicions. When McPherson was convicted as a sheep stealer at the Quarter Sessions, the Colonial Times

informed its readers about Collin’s recent sentence to the road gang and revealed that Griffiths had been tried four years earlier as a bushranger, along

with a gang of seven or eight other men. Despite the severity of this offence, he had not only escaped a hanging but had been made a constable.

32

Although the paper did not directly state it, readers would have inferred that Griffiths may have saved himself by giving up the information that hanged

his companions. By comparison, the Colonial Times argued that McPherson’s character was more trustworthy than either of the two constables, as Major

Gray must have had a good opinion of him when he employed him as his shepherd. Both Collins and Griffiths remained in the local force, Collins being

officially reinstated in July. It is the only recorded instance in the bench book of constables successfully catching suspected offenders while they were

committing a felony.

The paradox of the convict constables lay in the need for them to be able to exert appropriate control over others, while displaying subservience to their

officers and the magistrates in keeping with their lower class and their prisoner status.

33

It took considerable skill for constables to be constantly

negotiating this dangerous ground as two of them discovered one evening on the Main Road, while shifting a convict public works gang to a new location.

Constables Isaac Bowater and Richard Cloak had unhitched their bullock carts and set up their night camp at Snake Banks on Captain William Wood’s

land. Wood, the local magistrate, sent his son to enquire who they were. John Wood made his enquiries circumspectly, perhaps used to the growing

assertiveness of convict workers. As he explained to the court, “I went down and asked them if they had leave to stay there and told them if they did not

ask permission I could take the bullocks to pound. Cloak said in a very indifferent manner they should not leave till tomorrow morning and that I should

not impound the bullocks. I left them and returned to my father and acquainted him with what had occurred”. Not satisfied with this lack of respect and

continuing refusal to seek his permission to camp, Captain Wood and his overseer rode down and told them to leave. Capt Wood met with the same

assertiveness. When confronted with the demand, Cloak once more replied that he would not leave until the morning. As Captain Wood explained, “I then

directed my sons to get their horses and take the bullocks to pound. One of my servants took one of the prisoner’s horses. The prisoner Bowater said

something to the servant, which I did not hear, it induced him to call me up. I desired Bowater to immediately tell me his name. He knew me to be a

magistrate. I am a constable, constable Bowater. This he said in a contemptuous manner and turning upon his heel walked off saying to the overseer, “it

is of no use saying any more”.

34

What makes this confrontation interesting is that it happened within earshot of the road gang. Bowater and Cloak knew they would lose credibility if they

backed down and insisted on their right to camp there as they were on government business. Wood, however, was furious that his authority as a

landowner, gentlemen and magistrate had been challenged by two serving convict constables. The confrontation provides a good illustration of the

ambiguous role of the convict police and the tensions that would rise when they tried to assert the authority that had been vested in them. Local

magistrates were aware of these tensions, but also seemingly unable to resolve them either. Peter Murdoch, captured this when he told the Molesworth

Committee that “I think Colonel Arthur had got the police of the colony to a very high pitch of discipline, but still it was not less disagreeable to the

feelings of us as independent magistrates.”

35

Convict police lacked the moral authority to pursue their role fully and the class authority to subject the

middle class to their orders.

Although there is some evidence, mostly reported in newspapers, that some police rough handled or beat suspects, they were also the victims of beatings

which added greatly to the stress of their jobs.

36

The general level of violence and drinking amongst some working class men in Britain and the colonies

may have been a contributing factor to this.

37

The physical brutality of the convict system may have exacerbated this further, by accustoming men to

receiving and perpetrating violence. Some convict police were caught in this cycle of violence as they could be both perpetrators of violence against other

convicts and victims themselves. An examination of the conduct records of local constables showed that many of them had been flogged at least once

during their career as police, while suspended and under punishment in road gangs.

As well as receiving institutionalized floggings the police were sometimes beaten quite severely by emancipists while they were performing their duties.

During 1835 seventeen attacks on police were reported. Not many of the minor attacks were prosecuted and were probably a reflection of the general

levels of violence in the community. In most cases the assailant was drunk. In January, Ellen West struck Constable MacManus when he found her running

from constable West’s hut while drunk after a probable domestic dispute.

38

Another constable was later threatened with a knife when he tried to arrest an assigned carter on a farm. The man had arrived back very drunk with two

other assigned men, after completing some deliveries with the farm cart. He refused to leave his hut and two other assigned servants had to help to

disarm him. Despite this, his actions did not appear to pose a serious threat to the constable.

39

Later that year, a drunken emancipist assaulted constables West and Johnson in the police office. West said in evidence:

Yesterday during the time the business of the office was going on, the prisoner came near the office door. He was very drunk. I told him to go

away. He said; "B---gger you and Mr Whitefoord (police magistrate) too.” I seized him by the collar and he struck me several times. With the

assistance of Cons Johnson, whom he also assaulted, and others, we succeeded in lodging him in gaol.

40

Other assaults offended public decency more. Two men who were drunk and fighting at the church service one Sunday morning had to be forcibly

removed by two constables, who were assaulted in the process.

41

These assaults seem to be part of the general round of police work and one of the

hazards of the job, often an illustration of the resentment with which convicts viewed police.

More severe assaults on police were the result of particular police investigations and prosecutions. Neighbors called police to intervene when Ellen

Gregory, the stonemason’s wife was being beaten by her husband’s assigned assistant, Edward Evans. As Evans was being taken to the watch house by

three constables, they were intercepted by Gregory and his employee Bradford. Constable Holden told the magistrate: “when Gregory came up he

demanded that we should give up his servant. I explained to him that we had taken him up for beating his wife. I am sure it was Gregory that kicked me

and broke my ribs. Bradford just struck me with his fist under the ear”. Holden described the severity of the beating and explained when asked, “I was ill

for a fortnight and two days from the effects of the treatment I received. I have not recovered from the bad usage I met with. I cannot walk without

a stick”.

42

Sometimes, constables preferred to disregard minor incidents of disorderly behavior. Constable Patrick Flynn of Ross was passing the Robin Hood inn,

the main drinking spot of convicts, when he was followed and taunted by an emancipist drinker. Ironically he ignored the man’s behavior, but one of the

important landowners riding by, commanded him to do something about the man’s bad language. Flynn explained in evidence: “he (Love) struck me

violently in the face with his clenched fist. I was taking him to the watch house when Sweet came out of Dickenson’s Public House. He laid hold of me and

said:" Let the man go." I said I will not leave hold him by the collar. He then struck me two or three times and kicked me violently”. Neither Captain

Horton, who had first complained, nor other bystanders gave Flynn assistance, but Horton did ride to the watch house and got police help. When they

returned, Horton recorded that, “the two men had then got the constable down and were pegging away at him as hard as they could. The other

constables came up and they were secured. The constable was very badly used and I think he would have been very badly treated indeed had I not been

there”.

43

Although a more considered opinion may have conceded that the incident would never have occurred, if Horton had not insisted that Flynn

arrest Love in the first place.

Sundays and evenings were key times for assaults on constables and women, as they provided the leisure time for men to drink and fight. Police were

also vulnerable on other holidays and around public houses at all times of the year. In particular, fighting was common if police tried to empty out public

houses especially at Christmas time in Ross.

44

Most of the severe assaults on police happened in Ross, where the institutionalized flogging of gang

members, appeared to escalate violence in the community, by former gang members who settled there.

Police were also likely to be injured when attending fights around the villages between drunken emancipists or ticket of leave men. Respectable people

were likely to call police to intervene and this level of vigilance may have helped reduce the number of serious assaults, as only around fifteen resulted in

court appearances. All assaults on police were likely to be reported by them though, if only to explain how uniforms became torn or injuries were

received.

Other stressful conditions affected the quality of the work of the convict police. Low pay made it difficult for convict police to afford to live honestly and

the records of the local Court of Requests show that some had to borrow money from local lenders while waiting for their monthly pay. Campbell Town

petty constables received between ₤ 28 - ₤32 per annum from 1828 to 1840 and rarely more than an additional ₤2-₤3 from arresting drunks or

apprehending absconders.

45

Few convict police were married, unlike the British Metropolitan police where 75% were married men.

46

Most Campbell

Town police were unmarried and subjected to the stresses of barracks life, or were rostered to live in the police huts at remote locations. The three or

four who were married appeared to have lived separately in huts or rented houses in the village. A handsome brick terrace of three houses, Gloucester

House, was commenced in 1836 in Church Street, Campbell Town. This was an attempt to attract more married police and also a symbol of the middle

class respectability that the police magistrate hoped to encourage amongst his constables.

The system of convict police never functioned as efficiently as Arthur boasted to his superiors in the Colonial Office. It was weak on detection and

relatively inefficient on surveillance, even though the idea of police outposts commanding the rural roads seemed like a reasonable plan. New chums who

absconded could be more easily stopped and apprehended on the roads than seasoned convicts who knew the ways of the colony, the back roads and

the bush. For old lags there were many spaces inbetween through which they could travel where police, soldiers and settlers rarely went. There were also

many safe huts off the beaten track where they would be welcomed and sheltered.

And yet, the convict police created a semblance of control, especially in rural areas like the Campbell Town district, largely through the fear they inspired.

They knew the local population well: they heard rumors about the assigned convicts and emancipists; convict informers knowingly or unwittingly assisted

them; they were well linked into the gossipy networks of information that circulated in the convict world. But their reputation was mainly based on bluff.

They were not encouraged to show initiative, were poorly trained and tightly disciplined. They functioned as an isolated social group, necessary to the

community but never welcomed as part of it. The more respectable they tried to become, the more this pretension was rejected by emancipists and

settlers alike, who would not accept their moral authority as convicts to enforce the law. Physically demanding and relatively poorly paid, their job was at

least as arduous as a soldier’s

© Meg Dillon 2008

Australian Colonial History

Chapter 4

More arduous than being a soldier? Convict police —

their work, leadership and the stresses of the job

This chapter will use the Campbell Town bench book to explore the

realities of police work in the mid 1830s. While previous historians have

catalogued many incidents of common police corruption, mostly compiled

from newspaper reports, there is a danger that the emphasis of the

existing literature will leave the impression that the force was ineffective.

As Sturma points out, there is a second danger too. Police corruption has

historically been a long run phenomenon and is certainly not limited to the

era of convict policing.

1

This chapter will attempt to rectify the deficiency in the current literature

by employing the magistrates’ bench records to explore the day to day

realities of convict policing in the 1830s, as the duties of the police

magistrate and his staff expanded during the period of Arthur’s

administration. The court records provide a means of exploring the ways

convict constables reacted to issues of loyalty, the power and class

struggles with local magistrates and abuses from other convicts and

emancipists. This chapter will approach the convict constables as people

caught for a moment in the public gaze, and demonstrate why the job of

policing a district was seen by some of their contemporaries as a more

arduous job than soldiering.

2

While the variety of police work had increased by the mid 1830s, putting

pressure on both superior officers and constables, the quality of active

policing was still in its infancy. Although Arthur argued their role was

“detecting” as well as control, there were few examples of successful

detecting in the 1835 bench book.

3

Such work was often left to the senior

officers if it was done at all. John Lyall was the acting chief district

constable when Henry Emmett, a local storekeeper, called him in to

investigate a suspected theft at his store. It must have surprised Lyall

considerably to discover that Emmett had almost completed the entire

investigation before he arrived. Indeed Emmett later used the court as a

stage to play out his powers of deduction almost as if suggest that the

local police and their commanding officer were far less capable than he in

resolving cunning thefts. Emmett delivered a masterly summary of his

efforts to the court, which contained more than a hint of irony. He charged

two of his assigned shop men with stealing 26 gallons of porter, 13 gallons

of Cape wine and 4 gallons of rum over a period of several weeks. The

quantity was too large for two men to consume without Emmett noticing

they were frequently drunk, so it was probable they had stolen the liquor

to resell it illegally around the village.

When he discovered his loss, Emmett removed the assigned servant, who

had been ordered to sleep in the storeroom to protect the goods, and had

another convict securely nail up the loft floor above the shop. He returned

secretly, late on the Saturday night, and placed some goods on top of the

liquor casks. On Monday morning he found the goods had been moved. In

addition, he explained to the court, “I felt assured the premises had been

entered and proceeded to examine the boards (of the loft floor)…I

immediately perceived one of the boards to be split, by which means it

was moveable at one end, and by moving it found a considerable opening

was made to the cow house below”.

Certain that he knew who the thieves were, Emmett sent for chief

constable Lyall, who arrived and searched the servants’ rooms, where he

found several bottles of spirits. Although this appeared to be proof

enough of their guilt, Emmett told the court that he continued to gather

evidence. “I afterwards examined some of the spirit casks, in particular a

cask of rum, which had been deposited with the store on Saturday last

only and found that something more than two gallons had been taken out

of it. From a cask of brandy I also found something more than one gallon

had been taken. I have compared the rum in the bottle produced by Mr

Lyall with a sample of that taken by me from a cask in the store, and I have

no doubt it is the same rum. I have not yet compared the brandy”.

4

Emmett had suspected a long standing and continuing robbery, taken

steps to prevent any further thefts, collected evidence of the break in,

questioned the suspects, noted their responses, and finally called in the

chief district constable.

5

Emmett’s investigation was more detailed than

any police investigation that was recorded in the magistrate’s bench book

for 1835 and implied that the concept of logical investigation was possible

in 1835, but more likely to be undertaken by the victim of a criminal act

rather than the police or their officers. The truth was that in a rural police

office the general round of duties left little time for sleuthing despite the

governor’s assertion that detecting crimes was one of the main duties of

his police.

Rural police magistrates gained more responsibilities as their office began

to function as the key local bureaucracy responsible for a range of duties

that later would fall under the jurisdiction of local government. Convict

control remained a substantial part of the duty of constables, particularly

the newly recruited. They performed escort duties, attended to fines, dealt

with disorderly persons, and enforced the growing numbers of regulations

about hawkers, carriers, bakers, coaches and permits for selling wine and

spirits.

6

But the convict police were the magistrates’ deployable staff and

had to gradually extend their duties from these tasks to many additional

functions. The increase in their duties sometimes perplexed their critics,

who thought that the primary function of the police was to exercise

control over the district’s convict work force and not to interfere with the

likes of free settlers.

By the mid to late 1830s, police magistrates were responsible for

supervising the work of district surgeons, rural postmasters and their paid

convict post messengers, local coroners and inspectors of stock. They also

made recommendations to these appointments thereby exercising a

degree of local patronage.

7

They enforced the licensing laws and

prosecuted local publicans for harboring and serving convicts.

They established pounds and deployed constables to run these, an

unpopular duty, as farmers resented paying fines for stock that had

strayed and hated the Slaughtering Act which forced them to pay for

inspectors who verified the ownership of all stock slaughtered for meat.

The magistrates oversaw the local Courts of Request that settled small

debts thus creating security in everyday commercial transactions. The

magistrate’s office sometimes dealt with welfare issues concerning women

and children. Frederick Forth, police magistrate in 1836, for example,

received a letter from his district constable at Ross asking what could be

done to help a married free woman who had been turned out of doors

with a black eye by her husband who had been drunk for a week.

8

The

magistrate’s office also acted as a labour exchange responding to

desperate settlers seeking convict labour for the grain harvest.

9

The office

provided information about the availability of ticket of leave men, taken

from the monthly musters, and sometimes public works convicts could be

temporarily deployed to assist settlers to get their crops in.

In addition, some police magistrates could be expected to supervise and

assist extensive public works projects in their areas. Throughout the early

1830s the various police magistrates in the Campbell Town district

supervised the expansion and repair of police buildings in the government

compounds and at remote police outposts.

10

Superintendents of road

parties in the district were supported by local police who helped move

convict gangs and equipment to new sites, and new levels of co-operation

were initiated between the Roads and Bridges Department in Hobart and

local police magistrates, including the use of shared offices for police and

road project superintendents.

11

In 1836, police magistrate Forth, a former

military engineer, also acted as superintendent of the public works gangs

that built the Red Bridge in Campbell Town.

12

To cap things off, the role of keeping track of convicts also became more

complex as increasing numbers of forms were required by the Chief

Magistrate’s Office and larger numbers of assigned and ticket of leave

convicts came to work in the district. Annual convict musters, monthly

ticket of leave musters, abstracts of local absconders, weekly abstracts of

cases heard, depositions for particular cases, police characters (references

for convicts), travel passes, financial accounts and pay abstracts were just

a few of the dozens of documents that were produced or submitted to

Hobart from the police magistrates’ offices.

13

Preventative policing also

started to gain momentum by the late 1830s and some thorough police

campaigns were mounted in the Campbell Town district. For example, an

extensive sweep through bush land was conducted by police, to burn

temporary huts where absconders could shelter.

14

On another occasion,

over forty men, including police, participated in a search for a bushranger,

a costly exercise that ran over many days.

15

In an era of mounting demands the high turnover of convict police and

their officers, who rarely stayed for more than three years in a rural police

office, presented considerable problems. While officers had high

expectations of the constables’ performance of their duties, there were no

plans to train them beyond the imposition of a rigid system of military-

style discipline.

16

The arduous demands of these duties were described

by James Mortlock, who served as a rookie constable for several weeks

before persuading the police magistrate to transfer him to the less

strenuous position of watch house keeper. As Mortlock described it:

A petty constable being supposed continuously to patrol an appointed

beat, from eight o’clock in the evening until six next morning, anyone thinly

clad found the duty very severe, especially in a strange place, during a

dark, wet, cold night, the latter part of which he passed in a state of

shivering, hungry drowsiness, quite incompatible with effectiveness. The

hours of darkness should always be divided into at least two watches.

Those few weeks were extremely harassing; I cannot remember that any

period ever inflicted so painful a trial upon my fortitude…

17

The absence of active policing in preventing petty crime was seen by some

contemporary critics and later historians as evidence of a widespread

corruption. While this was likely in some cases, the lack of preventative

policing can also be interpreted as a lack of active leadership by local

superior officers as well as a failure to develop policing procedures that

actively investigated local crime. At this time, however, neither the new

British police services nor the colonial forces had reached a stage of

development, when leadership or policy goals could be clearly defined and

implemented across the force.

18

In Campbell Town, a heavy turnover of senior staff occurred between 1832

and 1836. The men who acted as police magistrate during those years

were local farmers, with business responsibilities, and each seemed to

attract a level of local support from different factions. Simpson and Leake

appeared to be remembered fondly by local emancipists as fair men. On

the other hand, some of justices of the peace criticized Leake for

preferring the testimony of convicts to the word of a gentleman. Leake’s

replacement, John Whitefoord, was a farmer from Oatlands, who

sustained strong criticism in local papers from the emancipist and small

trader factions, but was later appointed by Arthur to the permanent

position of police magistrate at Oatlands.

Captain Frederick Forth, a military engineer, followed him to build the Red

Bridge at Campbell Town and impose firm order. Forth had served on

Governor Arthur’s staff and was a professional colonial public servant who

arrived from a position in the West Indies. Forth managed the bridge

project well, but was dismissed by Governor Franklin in 1839 for failing to

adequately supervise the collection of quit rents in his office. His free clerk,

George Emmett, was at first charged with embezzling the funds but the

charges were dropped when it was discovered the money was not missing

but merely mislaid.

19

There was a strong suspicion that as well as putting

up a bond for the young Emmett, his friends may have also provided him

with sufficient funds to remedy the deficit and clear his name. His father

and brother had been similarly charged and escaped prosecution while

serving in other government positions.

20

The quality and commitment of the local chief district constables in the

mid 1830s was questionable too. There was little incentive for them to stay

very long in the job. Despite having the responsibility for the overall

management of the local police force, their small salary of ₤75 per annum

was generally supplemented by holding other official part-time positions

such as the summoning officer for the Court of Requests with

remuneration of ₤50, pound keeper or Inspector of Stock.

21

Some, like

Francis Small only stayed ten months in the job before obtaining the

better paid position of Superintendent of Convict Writers in Hobart in

February 1835.

22

Particular duties were unpopular with some convict constables. After the

comforts and camaraderie of the police barracks at Campbell Town or

Ross, the isolation and loneliness of a month’s duty reporting to James

Sutherland, the local magistrate on the Isis River was quite unwelcome.

Sutherland imposed strict control on the rostered constable who had to

report to him daily and whose off duty hours were spent alone at the

police hut situated on a neighboring farm. An incident in 1835

demonstrated how severely Sutherland dealt with any perceived breach of

duty. Sutherland explained to the police magistrate how he was “called out

of bed, by one of my servants, tapping very gently at my window, and

telling me, that the constable was at that moment, harboured in (Joseph)

Albany's bedroom.” Sutherland left the house immediately and

accompanied by his servant, William German, went out to the kitchen door

and confirmed that German’s information was correct.

William German had a busy evening. When constable Thomas Kirby

arrived for the start of his month at the Isis, he first delivered the mail to

Sutherland’s where German had overheard the cook, Albany, arrange to

meet Kirby later that evening. German went back several times to check

the kitchen and cook’s room to see what was happening and eventually

around eleven o’clock, he heard somebody talking in Albany's bedroom.

He went through the kitchen and surprised the two men demanding to

know: “What games do you call this. This I said in consequence of seeing

meat and potatoes. Kirby asked me to have some supper. I refused and

went and told the men, in the hut and they advised me to tell my master.”

After informing Sutherland, German was keen to ensure that Kirby didn’t

leave before Sutherland found him, “so I returned and held the kitchen

door. Kirby said Open the door—open the door. But I would not do so till

my master came.” Sutherland was not convinced by Kirby’s explanation

that he had lost the key to his handcuffs and had returned from the police

hut to try and find it, as he could have searched for it the next morning

when he reported for duty. Sutherland was scandalized that it was late at

night and that “Albany was entertaining Kirby with supper.”

23

Convict constables had to be careful. There was always someone, either a

settler or a fellow convict, who hated or mistrusted them and would try to

expose them to punishment. Police were caught between the two groups

and in many respects could trust no-one. From the court records it’s not

possible to deduce whether German was trying to pay back either the

cook or the constable, or even if he was one of those convict servants who

had aligned himself with his master’s interests and dobbed in fellow

servants for his own gain. Kirby clearly knew he was not supposed to

fraternize with Sutherland’s assigned servants, when he tried to buy off

German by inviting him to join them at supper. Whatever social contacts

constables made with the general convict class was likely to be viewed

with suspicion by their officers as it could potentially compromise their

loyalty.

24

The court records also don’t include enough information to

judge whether or not the magistrate suspected the friendship between

Kirby and Albany was more intimate than a simple social call, or more

criminal, and that the two were involved with theft or fencing goods.

Certainly the sentences given to both men suggest they were being

punished for more than having supper together. Albany was sentenced to

thirty five lashes and returned to the Crown for reassignment and Kirby

was suspended and spent six months in a road party before resuming his

police duties in Campbell Town. This harsh regime of isolation from both

the barracks and companionship throws some light on why another

constable later in the year begged the chief constable to relieve him of his

duty at Sutherland’s.

25

There were other cases where convict servants tried to manipulate their

master’s lack of trust of convict constables in the hope of gaining an

advantage. John Smith, a former baker, was employed as a convict javelin

man (guard) at the Campbell Town jail. One morning after the church

muster he came across John Maker outside the Blue Anchor inn. Maker

had worked for Henry Jellicoe, a local magistrate, for nine months and

confided to Smith that he wanted to leave Jellicoe’s employment and get

another master. Smith told him that the way to do it was to pretend to

abscond and that Smith could come and pick him up at a pre-arranged

spot. That way they could share the ₤2 reward that Smith would get for

Maker’s recapture and Maker would be returned to the Crown for

reassignment. The plan was enacted, however, Maker was sentenced to

Notman’s road gang instead of being returned for reassignment as he had

expected. A further unpleasant surprise was that Smith could not give him

the ten shillings he promised until he got his quarterly pay, but instead

gave Maker tea and sugar to take with him to the gang. Six months later,

Maker was released and assigned to another magistrate, John Leake, at

which point he pressed his claim for the ten shillings he was owed.

Maker not only wanted to get his own back on Smith, whom he believed

had failed to honor their agreement, but felt he could use his new master

to do so. He told the whole story to Leake, including his recent attempts to

collect the money owed to him. He confided that “about six weeks ago I

was in Campbell Town and I asked him (Smith) for money on account of

the absconding. He gave me half a crown. This was at the back of the

police office.” Maker told Leake he couldn’t provide a witness to this

conversation but when he asked Smith if that was all he was going to give

him, Smith replied “Yes, and if I was not contented he would give me in

charge if I asked for any more”.

Although Leake claimed he was initially dubious of Maker’s motives, he

was convinced when Maker explained that he didn’t tell Leake, “in order

that the javelin man might be prosecuted”, but that, “he thought it was a

scandalous thing when he had bolted that the man should only pay him

half a crown and then threatened that if he troubled him for anything

further he would take him into custody”. Apparently Maker’s sense of

outrage moved Leake to take action.

Leake advised Maker to make several applications in writing to Smith for

the 7/6d that he owed him but Smith again refused to pay up, telling the

man who presented the order that he didn’t know Maker. Leake sent

Maker back to Smith, with the groom accompanying him to act as a

witness to their conversation, but again Smith declined to pay up.

However, Smith was becoming suspicious of Maker’s persistence and

asked him how he came to serve the order in that way and kept the note.

The groom, when questioned later in court, was quite unhelpful to either

party in the matter, saying he had only seen the note passed to Smith but

hadn’t heard what they spoke about.

Meanwhile Maker claimed he had met Smith later, while he was droving

some sheep into the village and arranged to meet him near the jail where

he “gave me about a quarter of a pound of tea and about two lbs of

sugar.” By all accounts, either Smith felt he had paid off Maker sufficiently

with a half crown and two lots of sugar and tea, which apparently he had

taken from the jail’s supplies, or the tale was a fabrication.

26

The police

magistrate dismissed the case for lack of evidence thus avoiding

antagonizing Leake, one of his local magistrates, while at the same time

putting his convict constable—Smith on notice. Making something on the

side out of police work, if that was what Smith had actually tried to do, was

a lot more difficult than the critics of the police anticipated. Any

disgruntled convict with an axe to grind could complain against them and

at least get a hearing, apparently without much risk to themselves even if

they implicated themselves in an illegal transaction.

In any case, additional income from rewards for apprehending absconders

or drunks was actually quite modest if other rural districts were similar to

Campbell Town. The local courts processed around 110 men for being

drunk that year, which raised around ₤28 from the 5/- fines.

27

In addition,

constables apprehended around 36 absconders, so around ₤72 could be

distributed from the ₤2 rewards. Twenty one constables claimed rewards,

but most only apprehended one or two absconders during the year. Three

constables seemed more successful than most, although by October

senior officers were beginning to wonder if some constables were

deliberately losing prisoners they were escorting in order to try and claim

a reward for recapturing them. Constables Holden and Moore each

captured four absconders, but Moore was eventually fined for letting

prisoners escape. William Bowtell held the district record for capturing five

absconders.

28

However, most of the Campbell Town constables would

have been lucky to earn an additional ₤2 - ₤3 from rewards and fines in

1835.

Yet even if it was difficult to make extra money out of police work, some

police had information to exchange that they could use to their advantage.

Stock theft was rife in the district according to settlers, but few convicts or

emancipists were prosecuted for it. As chief constable Lyall found out, they

operated at night and in out of the way places which made them too hard

to catch in the act. Perhaps convict constables at Lake River or St Pauls

Plains had suspicions or even firm information about some local

characters, if they did, they rarely appeared to follow it up.

However, this information could be a very valuable commodity of

exchange for a convict constable in trouble. Constable Richard Collins, a

former basket maker from Woolwich, was only twenty four years old when

he was sentenced to nine months with the Constitution Hill road party for

inducing two assigned men to buy him drinks at the Blue Anchor Inn in

Campbell Town. He had an excellent conduct record and this was the first

misconduct recorded against his name in the six years since he had

arrived in the colony.

29

Collins only stayed four weeks with the gang before absconding. Four

soldiers later testified they overheard him say “he would rather hang

twenty men to save his punishment on a chain gang”, and although Collins

denied using this phrase, it seems clear that his first experience with a

road party created a very strong incentive for him to avoid returning to his

punishment.

30

Collins remained at large for eight days at the end of

February, during which time he made his way back to the Campbell Town

district. There he gave himself up to Mr Davidson and Archibald McIntyre,

the divisional constable, on Davidson’s farm at Salt Pan Plains.

31

He

appeared before Magistrate Whitefoord and was initially arraigned to be

returned to the Constitution Hill road gang for sentencing.

Collins spent ten days in the Campbell Town jail waiting to be returned to

his gang, and during this time he and constable Thomas Griffiths devised a

plan. Collins told the police magistrate that he had valuable information

that could convict sheep stealers at St Pauls Plains on the property of the

magistrate, Major William Gray. Eager to improve the local conviction rate,

Whitefoord ordered Collins to work with Griffiths at the Avoca police office

rather than returning him to Constitution Hill.

A fortnight later, the two constables staked out the hut used by a couple of

ticket-ofleave convicts named Macpherson and Spicer who worked for

Gray. Griffiths told the magistrate that early in the morning they saw

“James Macpherson and another person killing a sheep which proved to

be the property of Major Gray”. As they moved in to arrest them, one

escaped, but Macpherson was secured. They picked up a third man, James

Spicer, in the hut. Several days later, they apprehended William Duncan

whom they strongly believed “to have been the person who was with

Macpherson on the night in question.” As Griffiths put it: “He answers to

the description of Macpherson's companion in all respects. I can’t venture

to swear to him—having had no knowledge of the prisoner before, and the

night being dark”.

Collins could do little better. Although he believed Duncan to be the

culprit, he confessed that: “I can’t swear to him.” He reported, however,

that he had seen Duncan at Avoca, the night before the offence took place

and had seen him several times at Macpherson’s hut. Griffiths further

damned Duncan by claiming that, “the prisoner has told me he is night

shepherd to a person named Smith who bears a very indifferent character.

He left the neighborhood of Avoca directly the subject of sheep stealing

was made public”. Duncan countered these claims by providing an alibi of

sorts for the night. According to his testimony he had stayed with Robert

James and Paddy Sullivan at Avoca “from dark at night to sunrise” and

volunteered that Sullivan at least had been sober.

Given the fragility of the evidence, Police magistrate Whitefoord acted with

caution. All three men had their tickets of leave suspended. Duncan was

given some benefit of the doubt. He was sent to the town surveyor’s gang

in Launceston, one of the lighter punishment stations. The charge against

Spicer was dismissed as he had not been caught with the sheep.

Nevertheless, he was relocated to a road party for twelve months.

Immediately, however, the case raised public suspicions. When McPherson

was convicted as a sheep stealer at the Quarter Sessions, the Colonial

Times informed its readers about Collin’s recent sentence to the road gang

and revealed that Griffiths had been tried four years earlier as a

bushranger, along with a gang of seven or eight other men. Despite the

severity of this offence, he had not only escaped a hanging but had been

made a constable.

32

Although the paper did not directly state it, readers

would have inferred that Griffiths may have saved himself by giving up the

information that hanged his companions. By comparison, the Colonial

Times argued that McPherson’s character was more trustworthy than

either of the two constables, as Major Gray must have had a good opinion

of him when he employed him as his shepherd. Both Collins and Griffiths

remained in the local force, Collins being officially reinstated in July. It is

the only recorded instance in the bench book of constables successfully

catching suspected offenders while they were committing a felony.

The paradox of the convict constables lay in the need for them to be able

to exert appropriate control over others, while displaying subservience to

their officers and the magistrates in keeping with their lower class and

their prisoner status.

33

It took considerable skill for constables to be

constantly negotiating this dangerous ground as two of them discovered

one evening on the Main Road, while shifting a convict public works gang

to a new location. Constables Isaac Bowater and Richard Cloak had

unhitched their bullock carts and set up their night camp at Snake Banks

on Captain William Wood’s land. Wood, the local magistrate, sent his son

to enquire who they were. John Wood made his enquiries circumspectly,

perhaps used to the growing assertiveness of convict workers. As he

explained to the court, “I went down and asked them if they had leave to

stay there and told them if they did not ask permission I could take the

bullocks to pound. Cloak said in a very indifferent manner they should not

leave till tomorrow morning and that I should not impound the bullocks. I

left them and returned to my father and acquainted him with what had

occurred”. Not satisfied with this lack of respect and continuing refusal to

seek his permission to camp, Captain Wood and his overseer rode down

and told them to leave. Capt Wood met with the same assertiveness.

When confronted with the demand, Cloak once more replied that he

would not leave until the morning. As Captain Wood explained, “I then

directed my sons to get their horses and take the bullocks to pound. One

of my servants took one of the prisoner’s horses. The prisoner Bowater

said something to the servant, which I did not hear, it induced him to call

me up. I desired Bowater to immediately tell me his name. He knew me to

be a magistrate. I am a constable, constable Bowater. This he said in a

contemptuous manner and turning upon his heel walked off saying to the

overseer, “it is of no use saying any more”.

34

What makes this confrontation interesting is that it happened within

earshot of the road gang. Bowater and Cloak knew they would lose

credibility if they backed down and insisted on their right to camp there as

they were on government business. Wood, however, was furious that his

authority as a landowner, gentlemen and magistrate had been challenged

by two serving convict constables. The confrontation provides a good

illustration of the ambiguous role of the convict police and the tensions

that would rise when they tried to assert the authority that had been

vested in them. Local magistrates were aware of these tensions, but also

seemingly unable to resolve them either. Peter Murdoch, captured this

when he told the Molesworth Committee that “I think Colonel Arthur had

got the police of the colony to a very high pitch of discipline, but still it was

not less disagreeable to the feelings of us as independent magistrates.”

35

Convict police lacked the moral authority to pursue their role fully and the

class authority to subject the middle class to their orders.

Although there is some evidence, mostly reported in newspapers, that

some police rough handled or beat suspects, they were also the victims of

beatings which added greatly to the stress of their jobs.

36

The general

level of violence and drinking amongst some working class men in Britain

and the colonies may have been a contributing factor to this.

37

The

physical brutality of the convict system may have exacerbated this further,

by accustoming men to receiving and perpetrating violence. Some convict

police were caught in this cycle of violence as they could be both

perpetrators of violence against other convicts and victims themselves. An

examination of the conduct records of local constables showed that many

of them had been flogged at least once during their career as police, while

suspended and under punishment in road gangs.

As well as receiving institutionalized floggings the police were sometimes

beaten quite severely by emancipists while they were performing their

duties. During 1835 seventeen attacks on police were reported. Not many

of the minor attacks were prosecuted and were probably a reflection of

the general levels of violence in the community. In most cases the

assailant was drunk. In January, Ellen West struck Constable MacManus

when he found her running from constable West’s hut while drunk after a

probable domestic dispute.

38

Another constable was later threatened with a knife when he tried to

arrest an assigned carter on a farm. The man had arrived back very drunk

with two other assigned men, after completing some deliveries with the

farm cart. He refused to leave his hut and two other assigned servants had

to help to disarm him. Despite this, his actions did not appear to pose a

serious threat to the constable.

39

Later that year, a drunken emancipist assaulted constables West and

Johnson in the police office. West said in evidence:

Yesterday during the time the business of the office was going on,

the prisoner came near the office door. He was very drunk. I told

him to go away. He said; "B---gger you and Mr Whitefoord (police

magistrate) too.” I seized him by the collar and he struck me several

times. With the assistance of Cons Johnson, whom he also

assaulted, and others, we succeeded in lodging him in gaol.

40

Other assaults offended public decency more. Two men who were drunk

and fighting at the church service one Sunday morning had to be forcibly

removed by two constables, who were assaulted in the process.

41

These

assaults seem to be part of the general round of police work and one of

the hazards of the job, often an illustration of the resentment with which

convicts viewed police.

More severe assaults on police were the result of particular police

investigations and prosecutions. Neighbors called police to intervene

when Ellen Gregory, the stonemason’s wife was being beaten by her

husband’s assigned assistant, Edward Evans. As Evans was being taken to

the watch house by three constables, they were intercepted by Gregory

and his employee Bradford. Constable Holden told the magistrate: “when

Gregory came up he demanded that we should give up his servant. I

explained to him that we had taken him up for beating his wife. I am sure

it was Gregory that kicked me and broke my ribs. Bradford just struck me

with his fist under the ear”. Holden described the severity of the beating

and explained when asked, “I was ill for a fortnight and two days from the

effects of the treatment I received. I have not recovered from the bad

usage I met with. I cannot walk without

a stick”.

42

Sometimes, constables preferred to disregard minor incidents of

disorderly behavior. Constable Patrick Flynn of Ross was passing the Robin