© Meg Dillon 2008

Australian Colonial History

Chapter 5

The Outsiders - Cash & Safe Huts

The Trade with Absconders

By the mid—1830s one third of all serving convicts were employed on public works, either directly under privileged conditions, or incarcerated in gangs

and penal stations. This chapter will focus on the widely practiced activity of absconding from road parties. Absconding was relatively easy and many men

ran in order to spend some time away from their gangs, and a few, to attempt to evade recapture completely. The chapter will look at the general patterns

of absconding across the island, including the ages of the men who absconded, how long they had been in the colony and whether they left and were

captured singly or in groups. One of the main drivers of absconding was the ready availability of cash that circulated within road parties, and without

which most would have been unable to pay for their periods of freedom outside the gang. It enabled them to purchase accommodation at safe huts

throughout the island and buy food, liquor and the conviviality that was provided in the huts away from the rigid work schedules of the gangs.

The chapter will discuss the effects of absconding on the Campbell Town Police District through an analysis of the eighty or so cases of absconders who

were recaptured within the district. Most absconders came from outside the Campbell town area and not all were quickly recaptured. Some cases reveal

the strategies of the more successful absconders. An accurate network of information about the locations of safe huts, costs of accommodation and

introductions to suppliers of goods and services circulated within the road parties. This chapter looks at how and where these services were supplied in

the Campbell Town Police District and how the cash earned by convicts in gangs became redistributed throughout such remote rural districts. The chapter

concludes by looking at how one such network was closed down by the police magistrate, and his public shaming of a number of large landowners who

had failed to fully supervise the activities of their shepherds.

By the mid 1830s Governor Arthur’s management model for male convicts had succeeded in establishing a stratified labour system across the colony.

Both a private and government labour force existed. The government provided masters with assigned convicts who mostly worked as agricultural

labourers. Masters were not permitted to punish their convict workers but were required to charge them with an offence before the local magistrate. If a

master found a convict worker repeatedly lazy or incompetent, he could return the prisoner to the government. Repeated appearances before a

magistrate, on more serious charges such as fighting, threatening an employer or fellow workers or assaults, would result in short sentences of three to

eighteen months in road parties, or more severely, in chain gangs working on the roads. A small number were ganged several times, before eventually

receiving a sentence of a year or more to a penal settlement. By the mid 1830s all penal sentences were served at Port Arthur, as the stations at Maria

Island and Macquarie Harbor had been closed. Within the ganged workforces in road parties and penal settlements, flogging was commonly used to

compel compliance and increase work outputs. The management strategies of ganging and flogging were borrowed from the institutions of slavery and

military service and were used to create fear and compliance amongst the majority of male convicts working for private masters and the government.

1

Although some convicts and contemporaries compared convicts to slaves, technically they were not. Their labour had been appropriated and supplied, to

either the private or public sector only for the term of their sentence. They retained their British citizenship while under sentence and their working

conditions were highly regulated in regard to working hours, food rations, accommodation and clothing. Nevertheless, contemporaries and opponents of

transportation, such as Henry Melville, editor of the Colonial Times newspaper, argued there were some similarities between the two labour systems.

2

His depiction of transportation as ‘white slavery’ was meant to draw attention to common abuses as such as flogging and ganging, punishments that were

not commonly received by convicted felons in England. The slavery debate had been intense in Britain and her colonies in the early 1830s, as the British

Parliament after much debate and a long public campaign, had abolished the institution of slavery in all her colonies in 1832 and voted to pay ₤15 million

to compensate British slave owners in the Caribbean colonies who were required to free their slaves.

Historians from the 1970s onwards examined the structure and conditions of slavery and wrote extensively about the ways slaves manipulated their work

conditions and owners, many gaining some control over their lives. Although this literature provided some insights into how ganged men (whether slaves,

serfs, convicts or later prisoners of war) gained control over some aspects of their lives, in general, Australian historians concluded that the institutions

and operation of slavery and transportation were quite different, even though there were superficial commonalities in the way all ganged men were

controlled, worked and resisted.

3

If ganging was an effective deterrent that created a significant disincentive for convicts to disobey orders, an observer would expect to see only small

numbers of men sentenced to gangs. But in fact, ganging increased during Arthur’s administration. In 1828, 11% of all male convicts were ganged or

incarcerated as punishment and one historian estimated this had increased to at least 24% in 1834 and had risen to 31% of the male convict labour force

the following year.

4

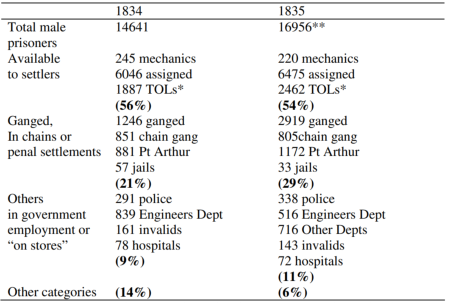

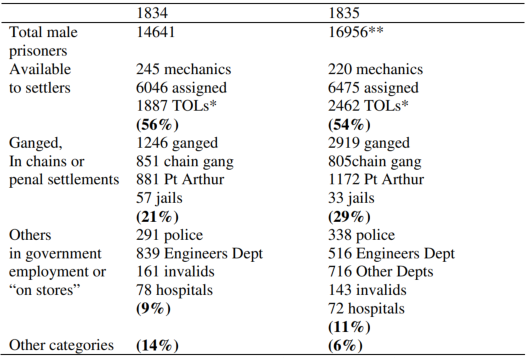

Other compilations of data shown in Table 5.1 suggest slightly lower rates, but are still high enough to demonstrate that increasing numbers of male

convicts were sentenced to ganging as punishment. It is not certain whether this was because convict resistance increased or because the administration

needed to expand the labour force needed for public infrastructure works and did so by handing down harsher punishments for trivial offences.

Table 5.1: Estimates of the numbers of male convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and their distribution to settlers, in gangs and

penal stations, and in other government positions.

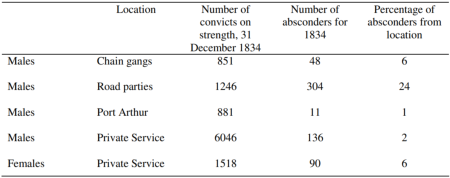

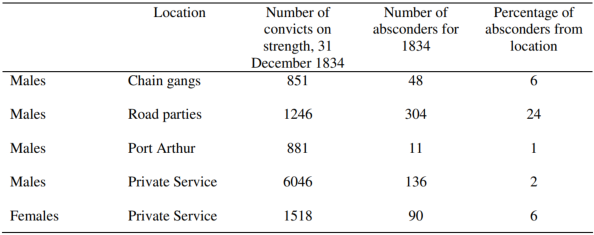

Sources: James Ross, Hobart Town Almanack and Van Diemen's Land Annual, Hobart Town, James Ross Printer, for 1835, pp. 47, 50-51 and for 1836, pp. 46, 51. Almanacks published the statistics for the previous year. *TOLs refer to ticket of leave convicts ie prisoners who were allowed to find paid work for themselves and live in the community, after a portion of their sentence expired. ** See Appendix 3. Almanack states there were a total of 15724 men in the Return for1835. This is an incorrect addition of the numbers of men then listed at various locations (16956). Mistakes in Convict Department convict numbers were frequent. Table 5.1 uses the correct total for all the men listed in the Return. Ganged convicts had to provide some sort of economic return to the administration to offset the high cost of keeping them and the colonial administration was keenly interested in using this labour resource to its best advantage. Governor Arthur, through the chief police magistrate’s office, reviewed most sentence recommendations from magistrates and frequently sent convicts to different road parties than those recommended by the local magistrates. Most of the road parties worked on the construction of the Hobart to Launceston main road and were housed at intervals along its path in temporary barracks. Other small towns such as Richmond, Green Ponds, Perth and Westbury had smaller road parties allocated to improve the roads leading to them. The size of the road parties varied greatly, even from one year to the next, as the Governor juggled the different priorities and the urgency of finishing particular stretches. 5 Most of the ganged men in road parties worked unchained under lesser sentences. Chain gangs were only located at a few of the road stations largely because of the high cost of having to house them more securely to stop them escaping. Historians have increasingly brought our understanding of convict gangs into sharper focus. Many earlier convict histories focused on accounts of the brutality in the road and chain gangs and penal settlements, where the lash and leg irons were evidence of a severe approach by convict administrations, intent on forcing men to reform. Robson, Manning Clark and Hughes endorsed this folkloric approach in varying degrees. 6 Hirst’s book Convict Society and its Enemies and Nicholas’s Convict Workers, a quantitative study of the records of 17,000 convicts to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land broke with the former traditions and set the agenda for more recent scholarship. Hirst redressed the balance by claiming that convicts often held the upper hand and were able to shape their material conditions. Nicholas was the first to propose a radical new perspective on the skills of convicts and the nature of the economy in which they laboured. Convicts were the colony’s first working class and offered a wide range of skilled and unskilled labour to private employers and the administration. Nicholas et al argued that generally convicts had been well treated, as they were valuable workers. As government workers, they built the infrastructure of both colonies and provided the middle level staff to manage and administer the convict system. They received fair treatment, good rations, adequate housing, medical care and reasonable working hours. 7 The bureaucratic model, devised to manage convicts working in road parties and other government jobs, had a fixed division of work regulated by rules and duties and was subjected to strict supervision by convict overseers, who reported on the performance of individual workers and the quota of work output achieved. Men were assigned to gangs or teams according to their skills and even many of the unskilled had opportunities to retrain as valuable workers. Control was maintained by using incentives to encourage convicts to achieve their weekly quota. Cruel punishment was rare because most ganged convicts responded either to incentives or the general removal of these privileges if they were uncooperative. 8 These assertions have been subjected to a great deal of subsequent scrutiny. While the narrow quantitative approach of Nichols et al has been widely criticized, the main thrust of their argument has been supported. 9 Two issues of concern remain. The first was that the ‘convict voice’ had become a casualty of the emphasis that Convict Workers place on quantitative data. 10 This criticism sponsored a growing number of case studies of individual convicts, where narratives existed that purported to be written by the convicts themselves. 11 Many of these texts were authored by convicts who had failed to cooperate with a work based system of punishment, and so had slipped down through the system into the increasingly severe punishments found in chain gangs and penal settlements. The second main criticism of Nicholas was that as the sources that he used were largely official statistics they provided little indication of the extent which convicts resisted attempts to make them conform. Penal stations, in particular, did not fit Nicholas’s benign model. It was in the administration’s interests to make these places as brutal as possible to control the majority of other convicts through fear. Regulations were flouted regarding hours of work and punishments were harsh. Consequently several types of convict responses emerged in penal stations: the iron men who cared nothing about punishment; the resisters who found ways of defying the system with a minimum of punishment; the collaborators who became convict managers- overseers, policemen, watchmen; and the silent servers who conformed to the rules. 12 Atkinson proposed a similar hierarchy of defiance from convicts who worked for private masters: verbal or physical attacks; appeals to a ‘just’ authority; withdrawal of labour; and compensatory retribution. 13 Taken together, these two schemas cover most of the responses by convicts to enforced labour and were probably used at some time by most of them, wherever they worked. In contrast to earlier histories, most historians of convict labour now see convict offence records as evidence of a dialogue between masters and the state on one hand, and convicts on the other. Defiance was not necessarily a response that all convict workers learned in the colonies. The label of ‘convict’ that historians impose on individuals, superficially strips a person of their rich former community roles, learnings and experiences and so can fail to acknowledge that resistance could be as deeply embedded in a convict’s former traditional community and working roles, as much as a reaction to the convict administration. The resistance debate also produced a series of responses that explored more fully the experiences of convicts in road and chain gangs and penal settlements. These revealed the diversity of jobs, opportunities and roles even in the most feared penal stations as well as in chain gangs and road parties. A convict with skills, or who could acquire skills, and who could manage his own behavior was potentially able to rise through the hierarchy of jobs in a punishment gang or penal station. A finely balanced set of incentives and disincentives operated even in these grim settings. But this balanced exchange between the administration and the ganged men was not always the case. McFie has demonstrated that while the administration required complete obedience from ganged workers in exchange for indulgences, it often failed to deliver its side of the bargain by not supplying the regulated levels of accommodation, food and clothing that men needed to work effectively. The Grass Tree Hill road party, charged with constructing the Risdon to Richmond road from 1833 to 1838, frequently experienced shortages of clothing and food. One result was that men were punished for stealing food and clothes from other prisoners as well as from houses and farms nearby. Men who were caught setting kangaroo traps to supplement rations were also punished. Shortages led to incidents of resistance when men refused to attend church, withdrew their labour a number of times in 1834 and in 1835 five men openly rebelled threatening soldiers with their pick handles before absconding. 14 By contrast, Maxwell-Stewart documented the importance of the very productive convict shipyards at Macquarie Harbour penal station and the complexity of the system of intermediate work gangs that supported this industry. Incentives such as extra rations, the right to leisure time fishing, separate living quarters for the shipyard workers, tobacco and tea rations were provided to encourage gangs that filled their work quotas. Skilled convicts, overseers, constables and clerks, received cash wages and better than average living conditions which they negotiated for their collaboration with the free managers. 15 The uncooperative worked in the two punishment gangs at unskilled work such as felling timber and rafting it back to the main settlement; a further gang, containing former absconders, worked in irons turning the mill wheels to grind flour. A thriving camp black market provided mechanisms for the illicit exchange of surplus or stolen food and goods, the chief currency being bread. Maxwell-Stewart saw no contradiction between Nicholas’s concept of convicts as workers even in places such as Macquarie Harbor, but argued that penal labour also existed as punishment, thus penal stations had both an economic and ideological function in the convict system and also that it was the unskilled ganged men who were less likely to win better conditions for themselves and more likely to stay in the worst jobs that attracted the highest punishment rates. 16 Two views emerged in colonial society by the late 1830s about punishment and reform. Arthur used his persuasive skills with the Colonial Office to try to convince them that he administered a model system which was characterized by a measure of certainty. He wanted to ensure that convicts knew with precision what punishments particular offences would attract and conversely the indulgences which would flow as a consequence of good conduct. 17 But it is when the indulgences and the punishments are weighed against each other that a sanguine model of convict life in a gang or penal settlement starts to come unstuck. Not all road parties or penal stations were administered with the same sense of fairness that Arthur required. Molesworth described them as places of “unmitigated wretchedness” and the former Chief Justice of New South Wales, Sir Francis Forbes, argued that, “the experience furnished by these penal settlements has proved that Transportation is capable of being carried to an extent of suffering such as may render death desirable”. 18 In this way, the system could work against itself. The more wretched the men were when sentenced to punishments in road parties, chain gangs or penal stations, the more they were likely to try to abscond. The rate of absconding for men varied depending very much upon where they worked. Table 5.2 shows that during 1834 only 2% of males absconded from private service despite two thirds of male convicts being employed as assignees or holding tickets of leave. By comparison, 24% of the road gang population absconded from their gangs, where the work was arduous, living conditions poor and escape was easy to make. The lower percentages of men who escaped from either chain gangs (6%) or Port Arthur (1.2%) is explained by the much tighter security under which the men were kept. Even so, it is surprising that 23 men in 1833 and a further 11 men in 1834, were able to abscond from Port Arthur, despite its highly publicized strategies to stop men from leaving the peninsula. 19Table 5.2: All absconders for 1834 from private service, gangs & Port Arthur penal station.

Sources: Government Gazette, weekly publication, 1 January 1833–30 December 1834, Hobart, AOT, Data taken from Matt Loone, XL Spreadsheet, Honors Thesis, University of Tasmania, 2005. James Ross, Hobart Town Almanack and Van Diemen's Land Annual, Hobart, 1835, pp. 47, 50-51. It is also worth noting that around eighty men absconded from government employment in 1834. 20 None of these convicts was working under a punishment sentence: many were skilled tradesmen working on public works, and it has sometimes been assumed that they worked under relatively good conditions with indulgences, some even being paid for their work. Amongst the sites they ran from were the colonial hospital, the Mt. Nelson signal station, the Survey Department, the Brig Isabella, the Commissariat Office and the Muster Master’s Office. Absconding represented a significant problem for the administration because around 6% of all males absconded during a year, even though most were recaptured relatively quickly. A small number, however, eluded capture for between one to four weeks and some remained at large for much longer. The 1835 General Muster of male convicts listed around 65 convicts, who absconded between January 1833 and December 1834 and were still at large in December 1835. The muster also recorded that around 3 convicts per year between 1804 and 1832 remained unaccounted for. 21 A general look at the men who absconded shows that most men ran only once a year, although there were a small number of men in all road gangs who absconded twice. Determined or serial absconders were rare and only 16 men, drawn from all employment sectors across Van Diemen’s Land, attempted to abscond 4 or 5 times in the 24 months of 1833 to 1834. 22 Most men absconded in the months of mild weather from February to May or at the peak times of planting or shearing for those in private service on farms during the months of August to October and again throughout December. They were mostly young men in their twenties who had only been in the colony three years or less. Only two or three men were aged in their forties and one aged 54 years. There were no mass breakouts from gangs, most ran singly or in pairs and seemed to split up on the road and go their own ways. There were three main factors that determined the rates of absconding. These were the ease or difficulty of leaving a site, the degree of unpleasantness in the work or living conditions the men experienced, and their access to cash to purchase food, clothes and shelter, while on the run. For example, a chain gang was normally locked down at night in a secure barracks. In addition to wearing irons the men were not permitted to work outside the compound for local settlers during weekends. 23 While they were able to illegally trade and barter for goods within the gang or penal settlement, their access to cash was restricted. By comparison, unchained men in road parties had the best opportunities to abscond. They could leave their gangs both during the work day and also at weekends, when many went to work for settlers. Many also had access to cash that they earned from weekend work. Like convicts in chain gangs they frequently experienced poor living conditions and strenuous work requirements. As a result there was plenty of incentive to leave, at least for short periods of time, in order to gain some relief from gang life. It is not therefore surprising that road gangs had the highest rates of absconding, for those who worked in them had both the motive and the opportunity to make a bid for freedom. The pattern of absconding was frequently different from the various road parties working on the highways. Almost all road parties experienced absconding, with the larger road parties having correspondingly larger numbers of men leaving them. Yet each large road party experienced different rates of absconding, which suggests that at various times, conditions in some road parties were worse than in others. Spring Hill road party had a population of 111 men in 1833, but only 21 men were recorded as having run. Grass Tree Hill with around only 50 men, had 30 absconders listed in the same year. Even in 1834, when both the Grass Tree Hill and Spring Hill road parties each had a complement of around 110 convict workers, 66 were listed as absconders from Grass Tree Hill, and on the other hand, only 24 from Spring Hill. Constitution Hill Road Party was one of the largest with a complement of around 180 convict workers, but had only 40 absconders listed in the 1833 Gazette. These rates of absconding seem insignificant when compared to Notman’s road party in 1833. One hundred and forty nine men absconded in 1833, yet this dropped to 69 the following year. These rates of absconding are not strictly comparable between gangs, as the sizes of gangs varied throughout each year, as did the total number of men, who arrived and were discharged from each gang, with short sentences of three to six months. Even so, in most large gangs, absconding was a continual nuisance for the gang superintendents. It also occurred in small gangs like Deep Gully with four absconders and New Norfolk with two in 1833, and Perth and Westbury with three each in 1834. Absconding was endemic throughout all road parties regardless of their size. 24 Continuous absconding had a significant impact on the Campbell Town district. This was not caused by district convicts absconding because fewer than twenty ran in 1833 and 1834 out of a population of around 900 men. Instead, relatively large numbers of convicts from road parties stationed outside the district were attracted to particular locations in the Campbell Town area. Most of these came from gangs at Spring Hill, Constitution Hill and Oatlands, which were larger gangs within 70 km of the Campbell Town. Of the sixty seven convict absconders apprehended and processed in the Campbell Town court during 1835, 18 were from Spring Hill, 13 from Constitution Hill and 12 from Oatlands. Several came from road parties that were further away: Notman’s road party at Green Ponds; Flat Top Hill; and the Sorell Rivulet; and one each from the Survey Department and the Green Point road party. 25 In addition to the larger road making gangs, a number of smaller gangs had been formed round the island in the mid 1830s. They were under the direction of the police magistrate’s officers and completed small tasks like building and maintaining stables and government huts, repairing footpaths or roads and gardening. Convicts who were apprehended in the Campbell Town Police District came from a selection of all of these types of government gangs, as well as from the larger road parties, where the work conditions may have been more onerous. Absconders also traveled down into the district from the north of the island too: five were from the Perth road party; four each from the Westbury road party and the Launceston chain gang; and three from the Launceston barracks. Some of the absconders may have been traveling through the district, but others appeared to treat it as a destination and got accommodation in remote shepherds huts where they paid in cash or goods and stayed for several nights or longer, depending upon what they could afford. Cash appears to have been one of the key drivers in enabling ganged men to abscond. Cash was more available to both convicts working in gangs and also to assigned men than we may have assumed and was probably the key factor that made absconders welcome in most of the remote shepherds huts. Despite Arthur’s regulations forbidding private employers to pay convict workers, many employers did so and used cash and extra rations as incentives to get satisfactory work from their convict workers. 26 The administration also paid some of its own convict workforce, such as convict police, clerks and specialized tradesmen, both in cash and extra rations that could be traded. Many convicts did not deposit the cash they earned in their government bank accounts despite the convict regulations that required them to do this. 27 Martin Cash the bushranger, wrote about the cash economy he observed when he arrived at the Restdown road party. He had brought ₤3 to ₤5 with him for contingencies and like other prisoners there was forced to pay one shilling for his supper of fat-cakes and boiled mutton if he wished to eat better quality food than the rations that were supplied. 28 John Davis of the Ross Bridge gang was searched on the street in Ross by a constable who discovered he was carrying five ₤1 notes and five Spanish dollars. 29 There is evidence that many convicts sold their good clothes en route to a gang. John Ellis, a ticket of leave blacksmith, observed one prisoner under escort selling a pair of trousers and some boots to another convict. 30 Two Quaker observers noted that many convicts arrived at the gangs “almost destitute of clothing”, a perpetual problem for gang superintendents who had limited supplies of new clothing and boots. 31 But more probably, most cash came into the gangs as wages earned by ganged convicts who also worked in a variety of jobs for local farmers and traders. Convicts in road parties, but not in chain gangs, were permitted to work on Saturdays and Sundays for local settlers. Most of the recorded cases in the 1830s indicate the men were paid in cash. Several men in the Grass Tree Hill gang worked for one Spanish dollar a week at reaping and threshing or for acting as watch keepers for local farmers. Another, who earned ₤2.12.0 for burning 3000 bricks for a local builder, paid the overseer twelve shillings to allow him to use the government cart. 32 Some Restdown gang members were employed casually by the local publican. 33 William Gates, while working in the Green Ponds gang, was offered work on a Saturday by a settler and got paid in tobacco, flour, sugar & tea, which he hid outside the camp to keep it safe. 34 Peter Peers absconded from Notman’s gang and returned to Campbell Town to claim wages of ₤6/17/9 that the local post master owed him for services Peers had rendered while he was a member of the Ross Bridge gang. 35 Another of the Grass Tree Hill gang, the gate keeper John Pett was described by the local magistrate as “a dangerous character, extremely cunning and possessed I am certain of much money.” Pett was employed casually by a local emancipist of bad repute. 36 As some of these examples suggest, some hut keepers and even gate keepers worked for settlers during the week while the ganged men were out on the roads and even overseers were willing to take kickbacks from the convicts to allow them to use government equipment. Cash and goods that came into the gangs helped fuel an internal black economy. Those earning outside wages or with excess goods to trade were able to employ other gang members to provide goods and services for them. Bewley Tuck from the Grass Tree Hill gang was charged with making clothes to sell and Ian Belcher a shoemaker was charged with making shoes for a settler’s family. 37 Cook house workers supplied special meals of meats, potatoes and baked bread to those who could afford them, instead of the standard meals of oatmeal gruel, damper and salt pork. Sometimes they increased their profits by skimming the stores meant for the ganged convicts or stealing directly from the commissariat store. 38 The Campbell Town bench book records also provide details of a number of local ‘laggers’, all ticket of leave men, who trafficked with gang members. James Johnson sold liquor to the Campbell Town foot gang, James Baird, a carter, bought lime from the Oatlands gang and William Nailor sold charcoal that the Ross government gang had produced, to a local blacksmith. 39 Finally, when William Fitzgerald bought 3000 shingles from James Hunt of the Grass Tree Hill gang, he was intercepted as he was driving the government cart to deliver the goods. 40 Trading inside gangs was a well established practice throughout the convict period. Even in the more isolated penal settlements, where contact with the outside world was more tightly controlled, internal trading between convicts took place. Maxwell–Stewart’s examination of trading circles at Macquarie Harbor demonstrated that bread was the internal unit of currency there, and services were provided amongst convicts with payment in bread or other goods. 41 A range of items were also regularly stolen from the stores or gangs’ tools to supply the demand. 42 Within the Grass Tree Hill gang, the blacksmith sold rum to men in the chain gang as well as loosening their chains for them and bread was sold for tobacco. 43 There were other ways of generating money within gangs. Overseers could extract payment from convicts who wanted easier jobs. 44 Clothing was stolen from nearby farms or from other gang members and sold. 45 Gang members could steal cash from each other, a common complaint in gangs that caused men to carry their cash with them, or hide it in the barracks or the bush outside. 46 Gambling also probably helped redistribute some of the cash in gangs. Men were locked in their huts at sunset with little or no supervision until morning. Games of chance played for money or goods could help pass the time although there were few prosecutions for it. 47 Observers sometimes commented that gambling was one of the chief recreations of the convict classes. 48 It is difficult to estimate how much cash circulated in gangs, but it could potentially be substantial. Conservatively, if in a gang of 100 men, thirty brought an average of ₤2 each when they arrived, and twenty of the gang each earned an average of ₤5 during the year for work they did for settlers, and another ₤40 was earned through gang members selling goods they produced to settlers, then this gang could have as much as ₤200 circulating in it for the year. In gangs where the trade with settlers was brisk and outside work was well paid the amount could be more. It was this money that enabled numbers of absconding gang members to buy services when they ran. The existence of remote shepherds’ huts in the Campbell Town police district was well documented in the Magistrate’s Bench book for 1835. In general magistrates and justices of the peace tried to discourage the trading that they believed took place there. They suspected that sheep duffing, trading in stolen goods, the selling of alcohol without a license, possibly prostitution and the sheltering of runaways was fostered in a number of huts. The support provided for runaways was part of a legitimate trade for many poor travelers who used the back roads and paid for cheap accommodation in the huts as the inns on the main roads were generally too expensive. These services were mostly, but not exclusively, supplied by emancipists and ticket of leave men as they had greater freedom than assigned shepherds to engage in commerce. While many farmers complained of the bad influence of these huts on the convict and emancipist population, it was difficult to prosecute their owners unless an unhappy customer complained to the police. The district police knew of many huts that they believed were run by men of bad character, but were unable to close them or prosecute. Captain Crear, the local justice of the peace, believed that sheep stealing, prostitution and harboring of runaways was taking place at James Reilly’s hut on Mr Whitechurch’s farm, “Belle Vue”, on the South Esk River. A surprise visit to the hut by police only netted a ticket of leave man who was prosecuted for consorting, even though he had stayed at the hut for several months, an activity for which he had his employer’s permission while mustering stock. Police glimpsed another two men and a woman in the back room of the hut, but the hut holder prevented the police from speaking to them, even though there was a suspicion the woman may have been a runaway. They were in fact a visiting peddler and his wife of no fixed address. 49 Evidence of illegal interactions between assigned convicts, runaways, ticket of leave men and emancipists emerged at “Ellenthorpe” farm, a property belonging to George C. Clark. While coming home from Ross in his carriage, Clark saw a man driving off some of his sheep in the direction of Black Tom’s hut. 50 . The man was later identified as John Wood a serial absconder from the Oatlands and Spring Hill road parties. Whenever Wood escaped he headed for Ross and Little Forresters Creek, as he had previously worked for a farmer there. While the police magistrate agreed with Clark that there was a great deal of circumstantial evidence that Wood was engaged in sheep theft, he sentenced Wood to 18 months at Port Arthur for absconding, as this was a charge which was much easier to prove. Despite his bad reputation Black Tom could not be prosecuted at all. 51 While certain huts had a bad reputation, in fact most of those used by emancipists were places where socializing, drinking, exchanging information and trading in goods and services could take place. 52 The subculture of convict hut life and the activities which took place there could be seen as a colonial counterpart of the less respectable working class districts in British cities where poor men and women could get cheap accommodation, socialize and make contacts for work or less legal activities. William Fisher’s hut on the South Esk River was raided by police who found Ann Harding, a female assigned convict servant, gambling there. Harding had not traveled far but despite this she was sent to Launceston women’s prison for absconding from her master. Fisher was fined ten pounds by the local magistrate for harboring a female absconder but the severity of the fine suggests the magistrate suspected Fisher was conducting a brothel but was unable to conclusively prove this. 53 For some convict men and women the lure of getting away from the drudgery of work and the need to socialize with their peers, away from the restrictions of the convict regulations, would be a motive strong enough to risk further punishment by absconding. However, huts were not always benign places where absconders could rely on secure and secret accommodation as long as they could pay for these services. Both hosts and guests sometimes abused the hospitality. William Buchanen was an assigned servant of G.C. Clark’s on Ellenthorpe farm when he was charged in November 1835 with “Suspicion of collusion with prisoners from Spring Hill and Constitution Hill road parties to abscond for the purpose of enabling him to collect reward.” Clark believed Buchanen had captured six absconders at different times and at least two others had escaped from him. This was a lucrative trade for Buchanan as the going rate for accommodation at safe huts in the area, including food and possibly grog, was around five shillings a day, although this was probably very negotiable. 54 Constables Eastwood and Johnson apprehended an absconder named Pearson at Black Jones hut who told him that after being sheltered by Buchanen, he agreed for Buchanen to hand him over to police if Buchanon paid him ten shillings of the reward. Constable Johnson reported to the magistrate that: I saw runaway Pearson apprehended by Eastwood He told us that he had run away from Mr Clarks shepherd meaning Buchanan the night before- because he had not got ready money to give him which he had promised, ten shillingsHe told us at the same time that another runaway had absconded with him and was in the Tier - Buchanan was to have given Pearce ten shillings when he got the reward, but he did not like to trust him- Pearson also said that if he would abscond again and go to Buchanan, he Buchanan would give him a pound and keep him three or four days at the hut. 55 Thomas Phillips, another convict shepherd of Clark’s was also stationed at the Three Mile Hut with Buchanen and provided more insights about the relationship between absconders and hut keepers. Some convict workers preferred to turn a blind eye to the activities that occurred about them. While this put them in jeopardy of being charged with harboring, this appears to be a risk that they were prepared to take rather then break ranks. Phillips, however, was willing to give evidence once the absconders had been captured. What he had to say was revealing. In his words: I am shepherd to George Carr Clark esq stationed at the three mile hut with Buchanan Fore (four) runaways were taken by Buchanan at two different times and taken to the hut, The two first came near the hut and the other two I found at the hut when coming home in the evening. They were sitting down one had his trousers off , the other was smoking- Buchanan was sitting down in the hut- one of the runaways made himself known to me his name was Chance. He said I wish I had known that you was here- you might as well have had us as this one meaning Buchanan- I told them I would not have anything to do with them - Buchanan went outside the hut to get a piece of stuff to mend the runaways trousers - Chance said: “If you like to look out I will clobber Buchanan and you might take me the next morning”- The runaway said he had been at Springhill and had bolted and had ten shillings given him by the man who had taken him- the runaways taken last said they had received ten shillings at the Hanging Sugar Loaf - meaning Buchanan. I had a word or two with Buchanan about his taking up my bed by bringing runaways there. Buchanan and himself went to bed and the runaways had some clothes from them to lay on the floor, they were not secured and could have gone away if they liked, but did not. 56 It would have been difficult for the police magistrate to know how truthful any of the witnesses were in such cases. Some convicts could be very pragmatic about the need to implicate others and minimize their own participation in illegal activities. The assignment system, with its policy of rewarding informers and paying bounties for handing in absconders, encouraged deception; and its harsh punishments encouraged pragmatism about personal survival. Whiteford did not charge Phillips but sentenced Buchanen to imprisonment with hard labour. Not only were the local emancipists and convicts able to provide services that aided absconders in the many remote huts of the district, but the local geography of parts of the district facilitated the secret movement of absconders across it, and provided many low-hilled wooded areas on the backblocks of farms, where hut keepers could offer absconders accommodation and where they were unlikely to be disturbed. The district was physically far less secure than Lieutenant Governor Arthur’s optimistic deployment of police and soldiers outposts suggested. 57 The police boxes and soldiers could be asily avoided by more experienced convicts who had knowledge of the tracks into the St Pauls Plains, Lake River and Jacobs Sugarloaf areas: the three most popular local areas that many absconders attempted to reach. Jacobs Sugarloaf was a hill high enough and distinct enough to be an excellent landmark for travelers. It was a magnet for absconders from the Spring Hill, Constitution Hill and Oatlands gangs, and many of them were familiar with the routes and tracks into this farming area between the Isis and Macquarie rivers, and the safe huts there that would welcome absconders. Men could travel in the bush beside the Main Road up to Tunbridge, then turn left on a small track to Jacobs Sugarloaf. This gave them access to the farms and the low scrubby hills that provided them with cover. The tracks could be completely avoided if the travelers traveled through the low hills on either side. The more remote shepherds’ huts were situated in these hills. The backblocks of the Dixon, Headlam, Brewer, Mackersey, Bayles and Wilson farms formed a natural corridor through this area. 58 A traveler could continue on to the Macquarie River and even as far as the remote Lake River. The geography of the area was perfect for travelers who wished to keep off the main tracks or linger out of sight. On 2 June 1835 speculation erupted in the district as five middle class farmers from the Jacobs Sugarloaf area were publicly brought before police magistrate John Whiteford and his justice of the peace, Henry Jellicoe, to answer charges of harboring absconders on their farms. The bench book does not record who laid the charges, but it is likely that it was someone of considerable social standing. A likely contender is Charles Viveash, another justice of the peace and recent settler who constantly patrolled Baskerville farm on horseback. 59 Jacobs Sugarloaf was situated by one of his backblocks and his farm shared borders with most of the farmers who were charged. 60 The charges were both a humiliation and a warning to Bassett Dixon, John Headlam, James Mackersey (son of the Presbyterian minister), Peter Brewer and George Wilson. No details of specific incidents were recorded in the Benchbook and all charges were withdrawn after each farmer appeared. They were discharged and ordered to pay costs. 61 After this incident, all farmers in the area were placed on notice to be more vigilant about who their shepherds entertained or be publicly called to answer. Many were likely to have conveyed this message forcefully to their assigned servants. By late June more information started to appear. William Hawes an assigned servant on the Bayles farm, gave up William Coe. Coe was a ticket of leave man from the district, who had escaped from custody the previous November while on a felony charge. Coe then gave up the hut keeper William Wates on the Rokeby farm, who in turn accused Coe of stealing a pair of trousers from him. Wates later withdrew this charge, but it suggests that Coe may have supported himself by stealing clothes and selling them to traveling hawkers. At the same time, a local emancipist, John Roberts, was given up by the free settler John Bayles, who accused him of stealing clothes and goods from his farm. Two local emancipists, John Bagles and Walter Hobson, also accused Roberts of stealing their clothes. These charges suggest that a well organized pattern of thieving helped support some absconders who were on the run in the district. 62 Joseph Bayles, subsequently captured two absconders from the Westbury road party that he found on the Rokesby farm on 24 June. They had only been at large for three days and appeared to have traveled straight to the area. 63 Local farmers also started to investigate thefts more closely. John Hedlam responded to his humiliation in the local court by arriving home and immediately investigating more vigorously the theft of a 100 lb bag of flour from his stores the previous month. He charged three of his assigned servants with the theft, claiming they took it from his stores and into the men’s hut. 64 As if to drive the point home, Whiteford also heard a case against another local farmer on 23 June. David Murray, owner of Gaddesden farm was frequently absent, tending to his business as a wine merchant in Launceston. 65 However, he was still responsible for the activities that took place on his property. Whitefoord received information that Murray had been killing and selling meat without a license. Other respectable settlers had also been charged at different times with flouting this unpopular regulation, but with Murray absent there may have been a concern that his farm had become friendly to absconders and was supplying blackmarket meats to the hut keepers who were sheltering them. 66 Murray was called to appear before the magistrate, but the information against him was withdrawn on 30 June and the case was dismissed. Whitefoord had worked hard to choke off the trade in essential supplies. He had put the district’s middle class farmers on notice that he expected them to be responsible for closely scrutinizing all the activities that took place on their farms. He had forced those masters, who like John Hedlam, were willing to accept small commercial losses as part of the free enterprise costs of their farms, to re-establish the penal nature of their control over their convict workers in place of the less formal traditional master and servant relationships that started to appear on some farms in the area. 67 A few absconders, who were captured in the Jacobs Sugarloaf area, had been at large for several weeks. This raised the suspicion that some of them may have been given up by the hut keepers who had sheltered them only after their money ran out. James Edwards returned twice to this area. He was at large for five weeks before he was captured on 5 July on George Scott’s farm on the Macquarie River near Ross. He escaped again from the Constitution Hill road party and was captured nearby on Mr Kermode’s farm on suspicion of housebreaking after being free for about three weeks. Thomas East had been free for about six weeks before his capture on Joseph Hedlam’s farm near Jacobs Sugarloaf in late June. John Macartney was caught after three weeks of freedom on Andrew Gatenby’s farm on the Isis River. The convict police, stationed at the Snake Banks police office on the Main Road north of Campbell Town, made many of their captures in the vicinity of their office or in Epping Forest. They almost always captured convicts from the Perth gang, the Westbury road party, the Launceston barracks and chain gang. Absconders, clothed in government slops, had few choices for evading the notice of the police unless they stayed off the Main Road and followed alongside it, hidden in the scrub, or moved southwards at night. 68 Even juveniles attempted to abscond, especially when assigned to remote farms. William Mason landed in September 1835 and absconded immediately after being assigned to a distant property on the South Esk River, and again three months later from the Perth road party where he had been next sent. His sentence was extended by twelve months and he was sent to Point Puer, a training station for juvenile convicts established across the bay from the Port Arthur penal settlement. 69 Surprisingly quite a few absconders were caught at Ross, either by the police, by the overseers of the Ross bridge gang or on the government farm. 70 One was taken by a soldier on duty in the town. 71 Although there was the disadvantage for absconders of a large police office and soldiers barracks situated in the town, there were plenty of emancipists around whom they could approach. However, there were many attractions in the village to entice them there, including local brothels, sly grog huts and the Robin Hood inn; a hostelry frequented illegally by many convicts from the Ross Bridge gang. Some may have hoped to blend in with the crowd of convicts in the Ross Bridge gang who worked in the village during the day. By comparison, few absconders were caught in Campbell Town. Other absconders had pressing personal reasons for leaving their gangs. William Jones, the convict post messenger from St Pauls Plains was picked up in Ross by constable Newton. Jones stated he absconded because he couldn’t support himself on the wages he received for his position as mailman. The Campbell Town bench was not sympathetic to this explanation and sentenced him to 50 lashes and sent him to a public works gang. 72 Paul Peers had a more compelling reason for absconding from Notman’s road party at Green Ponds and traveling up to Ross. He explained to the bench that he was there to recover ₤6/17/9 owed to him by William Rogers, the postmaster at Ross, for work done for him while Peers was a prisoner in the Ross Bridge gang. 73 These two wage related issues, also demonstrate the ways in which the assignment system channeled cash officially into serving convicts’ hands by paying some convicts for their services and also enabled convicts working in gangs to gain outside paid employment in their free time. In this case, a member of the local administration, the postmaster, felt quite at liberty to employ a convict for cash in much the same way as local farmers, blacksmiths and builders paid ganged convicts for goods or services. The township of Ross also provided many opportunities for petty thefts and for reselling stolen goods. Will Sawyer absconded from the Spring Hill Road party and had been successfully at large for five weeks before constable Holden apprehended him in Ross. He was remanded on suspicion of a number of felonies, none of which were listed in the charge. 74 Men, who had been on the run for several weeks, had to find ways of supporting themselves, when their cash ran out. However, absconders who tried thieving were at risk of being caught. 75 James Taylor and Abraham Powell, from the Oatlands public works gang, were apprehended after they stole clothes and other items from an emancipist draper in Ross. Police also charged Gilbert Dick, a ticket of leave man, with receiving the stolen goods. 76 A few absconders managed to find refuge along the South Esk River by making their way east to Avoca, Fingal and St Pauls Plains. Perhaps many from Launceston, Perth and Westbury were taken by the police at the Snake Banks police office before they got onto the South Esk track. Perhaps the stern reputation of the local justice of the peace, Major William Gray, at St Pauls Plains, the additional police office at Avoca, and one or two small contingents of soldiers in the area were effective deterrents. The geography was more hostile too. Hills along either side of the South Esk valley were higher and more heavily wooded than elsewhere in the district and settlement had been more recent. As well, it was not certain that the local Aboriginal population on the north side of the river had been pacified. 77 The continued presence of small contingents of soldiers in the valley testified to the settlers’ fears. Despite these disadvantages, a few absconders did make it through into the South Esk valley. One such was Henry Flack who had evaded the police for six months by traveling up the South Esk valley past Fingal to the Break o’ Day Plains, where he was finally apprehended by two constables, after his traveling partner and fellow absconder told police about his destination. 78 While most absconders were quickly apprehended, the more experienced convict absconders managed to stay at large for several weeks. In the Campbell Town district they either were brought in by farm servants after two or three weeks under the suspicion that their cash had run out, and they did a final deal with a hut keeper to share the reward of ₤2 for their capture. Or those less willing to return to their gang, tried to earn cash by stealing goods or stock and selling these to receivers. Depending on their success, they stayed at large for up to six months, but more generally, no longer than five weeks. Another smaller group of longer term absconders were also captured in the district and these men used quite different strategies. They generally traveled alone and sought to integrate themselves into the community by passing themselves off as free emigrants or emancipists. They supported themselves through paid work and appeared to avoid local criminal networks. The bench book gives very few details about John Bruce, formerly of the Oatlands public works gang, who had been at large for about a year, since the annual muster in 1834, when he was captured in the district. 79 Likewise John Poole, formerly of the Launceston Barracks, had been at large for sixteen months before being taken by constables Holden and Inglebert on 19 October 1835, about twelve miles from Ross. He then attempted to escape from the police several times before being escorted out of the district to serve a sentence at Port Arthur. 80 While we have no details about how either Bruce or Poole supported themselves during their periods of freedom, John Naldrett gave the magistrate a more detailed account of the two years he spent at large as an absconder. Naldrett had not been ganged, but had absconded from the service of a local magistrate, Richard Willis. Willis had charged him with an offence and Naldrett had received a flogging as punishment in the Campbell Town gaol. His experiences suggest it was sometimes easier than expected to use the main roads and not be picked up by the police. Naldrett was released from the gaol several days after being flogged and given a pass to return to Willis’s farm on the Main Road north of Campbell Town. He returned there, collected his belongings, including clothes and his ten shillings cash and absconded that night traveling south for Hobart. In Hobart, he immediately offered his services to a man he heard enquiring about a carter. He told the man he was a free man who had worked around Launceston and asked for ten shillings a week plus board. Five days after absconding from Willis’s, Naldrett was settled on his employer’s farm at New Norfolk in a new hut. He changed his name to Thomas Tickner and courted one of his employer’s convict servants, Sara Mills. After about five months Tickner got another job as a general servant to a shop keeper in New Norfolk. Three months later he sent a memorial into the Convict Department requesting permission to marry Sara Mills. Tickner described himself as a free man arriving on the ship Protector. Naldrett, as Tickner, was bold enough to get the Rev. Bedford to marry them at New Norfolk after the Convict Department gave its permission. Tickner claimed he was a widower at the time of his marriage. While free he had built up a credible profile of himself around New Norfolk and supported himself and his wife by successfully taking up several clearing leases, until arrested by two constables. By this time his wife had one baby who had died and was pregnant again. 81 Even though Naldrett had stayed away from the Campbell Town district during his period of freedom, there was always the risk that a former shipmate or workmate would recognize a fellow convict and give him up for the ₤2 reward. He was sentenced to a further twelve months with a road party. Even successfully absconding from Van Diemen’s Land did not always guarantee freedom. Charles Englebert, one of the police serving in the Campbell Town district in 1835, had absconded from Hobart in March 1827 after having frequented the Ship Inn and perhaps arranged passage with some of the seamen drinking there. He subsequently traveled to Port Jackson on the cutter Fanny. Six months later he was apprehended in Sydney and returned to Hobart on board the Emma Kemp, from which he briefly absconded again before recapture. Although this earned him a sentence of six months in a chain gang, it did not prevent him later being employed in the convict police force. 82 Indeed, John Naldrett also chose to become a convict constable after serving his sentence in the road party. 83 The trade with ganged absconders in the Campbell Town district illustrates how different the reality of the assignment system was from the picture that Arthur represented to the Colonial Office. He argued that road parties were the effective first level of a graded punishment system designed to persuade offenders to reform, but in fact, they were likely to have quite different effects on their inmates. Prisoners had to endure lice and scurvy, the general filth of huts and clothes, inadequate and unhealthy food and being forced to work beyond their strength, which all contributed to the “broken constitutions” of men who had served sentences in gangs. 84 The adverse psychological effects on these men were well known to contemporaries. One observer thought these punishments “deadened the human spirit” and that some men were “reduced to brute like apathy” when released. 85 A former magistrate felt that that “they become useless, and sink; that their physical force is gone by starvation, that their moral force is gone by the discipline, and that they become mere useless machines…” 86 Even though the full extent of these consequences were probably not intended by the Hobart administration, they were a feasible cause of so many ganged men having to find ways of providing sufficient necessities for themselves to survive. Ganged men often arrived with cash or took whatever paid work they could find to provide food and clothes for themselves. They stole from farms, trapped bush food and negotiated easier jobs, such as hut keepers or night watchmen, if they could get them. While gangs were not necessarily conducive to reform, they were most effective in teaching hard lessons about personal survival. By comparison, the often rough and dirty shepherds’ huts were enticing enough to cause many ganged men to run, even though they knew they would have to give themselves up when their cash or luck ran out. But the absconders’ trade also illustrates the loose control that the system exercised over convict men. Road gangs had a 24% absconding rate in the mid 1830s and beyond, because they were easy to escape from. 87 There could never be enough police, guards and soldiers to completely lock down the system, except in those exceptional locations such as chain gangs and penal stations. To a great extent the vast majority of convicts cooperated with the inefficient system of control by choosing to stay in private service or in road parties until they were released. For those convicts who were reckless or rejected this confinement, information about the back ways, the small bridle paths and the known safe huts provided an alternative way of enduring this misguided experiment in reforming them, by giving them occasional respite from the system amongst their own kind.

© Meg Dillon 2008

Australian Colonial History

Chapter 5

The Outsiders - Cash & Safe Huts

The Trade with Absconders

By the mid—1830s one third of all serving convicts were employed on

public works, either directly under privileged conditions, or incarcerated in

gangs and penal stations. This chapter will focus on the widely practiced

activity of absconding from road parties. Absconding was relatively easy

and many men ran in order to spend some time away from their gangs,

and a few, to attempt to evade recapture completely. The chapter will look

at the general patterns of absconding across the island, including the ages

of the men who absconded, how long they had been in the colony and

whether they left and were captured singly or in groups. One of the main

drivers of absconding was the ready availability of cash that circulated

within road parties, and without which most would have been unable to

pay for their periods of freedom outside the gang. It enabled them to

purchase accommodation at safe huts throughout the island and buy

food, liquor and the conviviality that was provided in the huts away from

the rigid work schedules of the gangs.

The chapter will discuss the effects of absconding on the Campbell Town

Police District through an analysis of the eighty or so cases of absconders

who were recaptured within the district. Most absconders came from

outside the Campbell town area and not all were quickly recaptured.

Some cases reveal the strategies of the more successful absconders. An

accurate network of information about the locations of safe huts, costs of

accommodation and introductions to suppliers of goods and services

circulated within the road parties. This chapter looks at how and where

these services were supplied in the Campbell Town Police District and how

the cash earned by convicts in gangs became redistributed throughout

such remote rural districts. The chapter concludes by looking at how one

such network was closed down by the police magistrate, and his public

shaming of a number of large landowners who had failed to fully

supervise the activities of their shepherds.

By the mid 1830s Governor Arthur’s management model for male convicts

had succeeded in establishing a stratified labour system across the colony.

Both a private and government labour force existed. The government

provided masters with assigned convicts who mostly worked as

agricultural labourers. Masters were not permitted to punish their convict

workers but were required to charge them with an offence before the

local magistrate. If a master found a convict worker repeatedly lazy or

incompetent, he could return the prisoner to the government. Repeated

appearances before a magistrate, on more serious charges such as

fighting, threatening an employer or fellow workers or assaults, would

result in short sentences of three to eighteen months in road parties, or

more severely, in chain gangs working on the roads. A small number were

ganged several times, before eventually receiving a sentence of a year or

more to a penal settlement. By the mid 1830s all penal sentences were

served at Port Arthur, as the stations at Maria Island and Macquarie

Harbor had been closed. Within the ganged workforces in road parties

and penal settlements, flogging was commonly used to compel

compliance and increase work outputs. The management strategies of

ganging and flogging were borrowed from the institutions of slavery and

military service and were used to create fear and compliance amongst the

majority of male convicts working for private masters and the

government.

1

Although some convicts and contemporaries compared convicts to slaves,

technically they were not. Their labour had been appropriated and

supplied, to either the private or public sector only for the term of their

sentence. They retained their British citizenship while under sentence and

their working conditions were highly regulated in regard to working hours,

food rations, accommodation and clothing. Nevertheless, contemporaries

and opponents of transportation, such as Henry Melville, editor of the

Colonial Times newspaper, argued there were some similarities between

the two labour systems.

2

His depiction of transportation as ‘white slavery’ was meant to draw

attention to common abuses as such as flogging and ganging,

punishments that were not commonly received by convicted felons in

England. The slavery debate had been intense in Britain and her colonies

in the early 1830s, as the British Parliament after much debate and a long

public campaign, had abolished the institution of slavery in all her

colonies in 1832 and voted to pay ₤15 million to compensate British slave

owners in the Caribbean colonies who were required to free their slaves.

Historians from the 1970s onwards examined the structure and

conditions of slavery and wrote extensively about the ways slaves

manipulated their work conditions and owners, many gaining some

control over their lives. Although this literature provided some insights

into how ganged men (whether slaves, serfs, convicts or later prisoners of

war) gained control over some aspects of their lives, in general, Australian

historians concluded that the institutions and operation of slavery and

transportation were quite different, even though there were superficial

commonalities in the way all ganged men were controlled, worked and

resisted.

3

If ganging was an effective deterrent that created a significant disincentive

for convicts to disobey orders, an observer would expect to see only small

numbers of men sentenced to gangs. But in fact, ganging increased during

Arthur’s administration. In 1828, 11% of all male convicts were ganged or

incarcerated as punishment and one historian estimated this had

increased to at least 24% in 1834 and had risen to 31% of the male convict

labour force the following year.

4

Other compilations of data shown in Table 5.1 suggest slightly lower rates,

but are still high enough to demonstrate that increasing numbers of male

convicts were sentenced to ganging as punishment. It is not certain

whether this was because convict resistance increased or because the

administration needed to expand the labour force needed for public

infrastructure works and did so by handing down harsher punishments

for trivial offences.

Table 5.1: Estimates of the numbers of male convicts in

Van Diemen’s Land and their distribution to settlers, in

gangs and penal stations, and in other government

positions.

Sources: James Ross, Hobart Town Almanack and Van Diemen's Land Annual, Hobart Town, James Ross Printer, for 1835, pp. 47, 50- 51 and for 1836, pp. 46, 51. Almanacks published the statistics for the previous year. *TOLs refer to ticket of leave convicts ie prisoners who were allowed to find paid work for themselves and live in the community, after a portion of their sentence expired. ** See Appendix 3. Almanack states there were a total of 15724 men in the Return for1835. This is an incorrect addition of the numbers of men then listed at various locations (16956). Mistakes in Convict Department convict numbers were frequent. Table 5.1 uses the correct total for all the men listed in the Return. Ganged convicts had to provide some sort of economic return to the administration to offset the high cost of keeping them and the colonial administration was keenly interested in using this labour resource to its best advantage. Governor Arthur, through the chief police magistrate’s office, reviewed most sentence recommendations from magistrates and frequently sent convicts to different road parties than those recommended by the local magistrates. Most of the road parties worked on the construction of the Hobart to Launceston main road and were housed at intervals along its path in temporary barracks. Other small towns such as Richmond, Green Ponds, Perth and Westbury had smaller road parties allocated to improve the roads leading to them. The size of the road parties varied greatly, even from one year to the next, as the Governor juggled the different priorities and the urgency of finishing particular stretches. 5 Most of the ganged men in road parties worked unchained under lesser sentences. Chain gangs were only located at a few of the road stations largely because of the high cost of having to house them more securely to stop them escaping. Historians have increasingly brought our understanding of convict gangs into sharper focus. Many earlier convict histories focused on accounts of the brutality in the road and chain gangs and penal settlements, where the lash and leg irons were evidence of a severe approach by convict administrations, intent on forcing men to reform. Robson, Manning Clark and Hughes endorsed this folkloric approach in varying degrees. 6 Hirst’s book Convict Society and its Enemies and Nicholas’s Convict Workers, a quantitative study of the records of 17,000 convicts to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land broke with the former traditions and set the agenda for more recent scholarship. Hirst redressed the balance by claiming that convicts often held the upper hand and were able to shape their material conditions. Nicholas was the first to propose a radical new perspective on the skills of convicts and the nature of the economy in which they laboured. Convicts were the colony’s first working class and offered a wide range of skilled and unskilled labour to private employers and the administration. Nicholas et al argued that generally convicts had been well treated, as they were valuable workers. As government workers, they built the infrastructure of both colonies and provided the middle level staff to manage and administer the convict system. They received fair treatment, good rations, adequate housing, medical care and reasonable working hours. 7 The bureaucratic model, devised to manage convicts working in road parties and other government jobs, had a fixed division of work regulated by rules and duties and was subjected to strict supervision by convict overseers, who reported on the performance of individual workers and the quota of work output achieved. Men were assigned to gangs or teams according to their skills and even many of the unskilled had opportunities to retrain as valuable workers. Control was maintained by using incentives to encourage convicts to achieve their weekly quota. Cruel punishment was rare because most ganged convicts responded either to incentives or the general removal of these privileges if they were uncooperative. 8 These assertions have been subjected to a great deal of subsequent scrutiny. While the narrow quantitative approach of Nichols et al has been widely criticized, the main thrust of their argument has been supported. 9 Two issues of concern remain. The first was that the ‘convict voice’ had become a casualty of the emphasis that Convict Workers place on quantitative data. 10 This criticism sponsored a growing number of case studies of individual convicts, where narratives existed that purported to be written by the convicts themselves. 11 Many of these texts were authored by convicts who had failed to cooperate with a work based system of punishment, and so had slipped down through the system into the increasingly severe punishments found in chain gangs and penal settlements. The second main criticism of Nicholas was that as the sources that he used were largely official statistics they provided little indication of the extent which convicts resisted attempts to make them conform. Penal stations, in particular, did not fit Nicholas’s benign model. It was in the administration’s interests to make these places as brutal as possible to control the majority of other convicts through fear. Regulations were flouted regarding hours of work and punishments were harsh. Consequently several types of convict responses emerged in penal stations: the iron men who cared nothing about punishment; the resisters who found ways of defying the system with a minimum of punishment; the collaborators who became convict managers- overseers, policemen, watchmen; and the silent servers who conformed to the rules. 12 Atkinson proposed a similar hierarchy of defiance from convicts who worked for private masters: verbal or physical attacks; appeals to a ‘just’ authority; withdrawal of labour; and compensatory retribution. 13 Taken together, these two schemas cover most of the responses by convicts to enforced labour and were probably used at some time by most of them, wherever they worked. In contrast to earlier histories, most historians of convict labour now see convict offence records as evidence of a dialogue between masters and the state on one hand, and convicts on the other. Defiance was not necessarily a response that all convict workers learned in the colonies. The label of ‘convict’ that historians impose on individuals, superficially strips a person of their rich former community roles, learnings and experiences and so can fail to acknowledge that resistance could be as deeply embedded in a convict’s former traditional community and working roles, as much as a reaction to the convict administration. The resistance debate also produced a series of responses that explored more fully the experiences of convicts in road and chain gangs and penal settlements. These revealed the diversity of jobs, opportunities and roles even in the most feared penal stations as well as in chain gangs and road parties. A convict with skills, or who could acquire skills, and who could manage his own behavior was potentially able to rise through the hierarchy of jobs in a punishment gang or penal station. A finely balanced set of incentives and disincentives operated even in these grim settings. But this balanced exchange between the administration and the ganged men was not always the case. McFie has demonstrated that while the administration required complete obedience from ganged workers in exchange for indulgences, it often failed to deliver its side of the bargain by not supplying the regulated levels of accommodation, food and clothing that men needed to work effectively. The Grass Tree Hill road party, charged with constructing the Risdon to Richmond road from 1833 to 1838, frequently experienced shortages of clothing and food. One result was that men were punished for stealing food and clothes from other prisoners as well as from houses and farms nearby. Men who were caught setting kangaroo traps to supplement rations were also punished. Shortages led to incidents of resistance when men refused to attend church, withdrew their labour a number of times in 1834 and in 1835 five men openly rebelled threatening soldiers with their pick handles before absconding. 14 By contrast, Maxwell-Stewart documented the importance of the very productive convict shipyards at Macquarie Harbour penal station and the complexity of the system of intermediate work gangs that supported this industry. Incentives such as extra rations, the right to leisure time fishing, separate living quarters for the shipyard workers, tobacco and tea rations were provided to encourage gangs that filled their work quotas. Skilled convicts, overseers, constables and clerks, received cash wages and better than average living conditions which they negotiated for their collaboration with the free managers. 15 The uncooperative worked in the two punishment gangs at unskilled work such as felling timber and rafting it back to the main settlement; a further gang, containing former absconders, worked in irons turning the mill wheels to grind flour. A thriving camp black market provided mechanisms for the illicit exchange of surplus or stolen food and goods, the chief currency being bread. Maxwell-Stewart saw no contradiction between Nicholas’s concept of convicts as workers even in places such as Macquarie Harbor, but argued that penal labour also existed as punishment, thus penal stations had both an economic and ideological function in the convict system and also that it was the unskilled ganged men who were less likely to win better conditions for themselves and more likely to stay in the worst jobs that attracted the highest punishment rates. 16 Two views emerged in colonial society by the late 1830s about punishment and reform. Arthur used his persuasive skills with the Colonial Office to try to convince them that he administered a model system which was characterized by a measure of certainty. He wanted to ensure that convicts knew with precision what punishments particular offences would attract and conversely the indulgences which would flow as a consequence of good conduct. 17 But it is when the indulgences and the punishments are weighed against each other that a sanguine model of convict life in a gang or penal settlement starts to come unstuck. Not all road parties or penal stations were administered with the same sense of fairness that Arthur required. Molesworth described them as places of “unmitigated wretchedness” and the former Chief Justice of New South Wales, Sir Francis Forbes, argued that, “the experience furnished by these penal settlements has proved that Transportation is capable of being carried to an extent of suffering such as may render death desirable”. 18 In this way, the system could work against itself. The more wretched the men were when sentenced to punishments in road parties, chain gangs or penal stations, the more they were likely to try to abscond. The rate of absconding for men varied depending very much upon where they worked. Table 5.2 shows that during 1834 only 2% of males absconded from private service despite two thirds of male convicts being employed as assignees or holding tickets of leave. By comparison, 24% of the road gang population absconded from their gangs, where the work was arduous, living conditions poor and escape was easy to make. The lower percentages of men who escaped from either chain gangs (6%) or Port Arthur (1.2%) is explained by the much tighter security under which the men were kept. Even so, it is surprising that 23 men in 1833 and a further 11 men in 1834, were able to abscond from Port Arthur, despite its highly publicized strategies to stop men from leaving the peninsula. 19Table 5.2: All absconders for 1834 from private service,

gangs & Port Arthur penal station.