© Meg Dillon 2008

Chapter 9

The Male Workforce: farm and village labour – working

for the Man.

In the past, historians have emphasized the power of the large land owners who had access to cheap land and convict labour and would draw on kinship

networks, influence in London and informal local networks with colonial officials.

1

By comparison, convicts seemed to have few means at their disposal to

combat the combined forces of State power and local paternalism. The rule of terror sanctioned by the colonial government in the form of flogging and

increasingly brutal penal discipline, seemed enough to force convicts to accede to the conditions of their servitude. This view fails, however, to account for

persistent convict resistance to many work conditions imposed on them, especially after the Bigge Report attempted to reposition convict labour by tying it

to the expansion of the wool industry in both New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land. By encouraging a class of small capitalists to invest in pastoralism

and providing a cheap supply of convict labour, the government unwittingly fostered the conditions for a classic class confrontation.

2

This was particularly

as the government enforced a contract with the land owners that not only required them to pay for the convicts’ keep in exchange for their labour, but also

required them to strictly enforce a rigid system of supervision and offer only a limited number of rewards to men and women who showed evidence of

reform.

3

Here an economic imperative and a moral one came into conflict, and for most large landowners the need for profit was likely to be the more

important of the two.

This chapter examines some of the compromises that grew out of this inherent contradiction. It first seeks to explore the recreational culture amongst

male convicts and the way that many employers and their assignees renegotiated the official prohibition of banning access to alcohol. The chapter

investigates the supply trail of illegal liquor that circulated in the district and the cash economy that thrived around it. The complexities of negotiating the

daily round of village work and coping with the demands of the agricultural seasons are also explored. While assigned males formed the primary rural

workforce in the Campbell Town district, the use of the growing numbers of ticket of leave holders as a supplementary workforce during periods of high

labour is also examined. This chapter will conclude by looking at the effects that their presence had on farm labour relations.

Although not all convicts drank, for many assigned workers drinking had cultural meaning. It marked the difference between work time and free time and

was often associated with a number of leisure activities which were enjoyed collectively. It was accompanied by gambling, singing, yarning, smoking and

reading and was probably almost always present when the men organized the popular pastimes of sparring, cock fighting or dog baiting.

4

Some also used

it to gain sexual favors from convict women. These activities grew out of traditional working class culture which was replicated in the colony although it was

often restricted to convict quarters, shepherds’ huts or other remote spots well away from the employer’s house.

5

Such social activities were important in

helping to redefine the likes of assigned workers as something other than convicts. For the men, free time on many farms marked a space into which

neither their employers nor the system should intrude.

6

Employers, who had managed farms in Britain, recognized a number of benefits that moderate drinking traditionally provided the rural labourer. Indeed

the provision of alcohol was often recognized as an important mechanism for creating a more harmonious work force and most masters turned a blind eye

to moderate drinking as long as it did not interfere with the men’s work or cause fights.

7

Their convict workers were capable of generating “an internal

cultural world” that maintained social links within their class traditions.

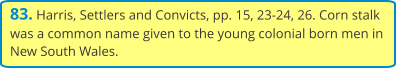

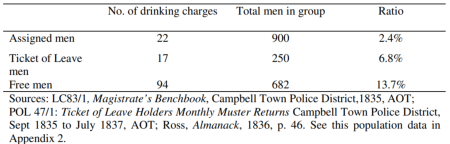

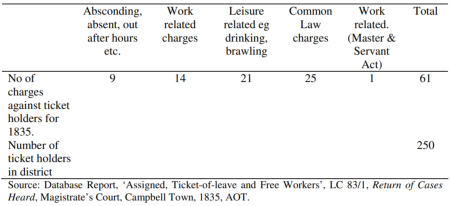

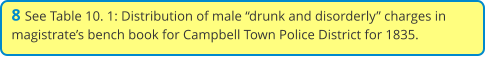

Although drinking was an important marker of class and by extension convict culture, it was not frequently prosecuted. Table 10.1 shows that assigned

men had the lowest percentage (2.4%) of prosecutions for drinking of any male group.

8

This does not necessarily indicate they did not drink, but it does

suggest that most assigned men, who drank, did so moderately or did not attract the attention of their employer, or their employer ignored this behavior.

A slightly higher percentage of charges (6.8%) were laid against ticket of leave men. Even so, fewer than one convict from the private sector labour force

was charged per week with being drunk and disorderly.

Some of the assigned men were picked up by the police while drinking in public on Saturday or Sunday. Dickenson’s pub at Ross was a strong attraction for

three of them. Charles Burdit confessed to the magistrate that “I got the drink at Dickenson's. The girl brought me a pint of wine which made me tipsy. They

did not ask me who I was. It was after church."

9

Thomas Bowles was also picked up on the street in Ross on a Saturday afternoon.

10

Another was caught

in the Christmas Day riot at Dickenson’s and got 40 lashes.

11

All were assigned to farms close to Ross and walked into the village in their own time and had

the cash to purchase drinks from the tap room of the public house. Likewise, drinking on the farm was only a problem for five or six employers who

charged their assigned workers. As five of the drinking charges occurred in August it is possible that some of the men received cash bonuses for the end of

the ploughing season and may have spent this on grog. Although this was the only appearance for each of the assigned men before the magistrate for the

year, the sentences varied considerably from admonishment to 25 lashes or three months with a road party.

12

This suggests that those who received the

more severe sentences were unsatisfactory in other ways which were not specified in the charge.

Again only five farmers charged their ticket of leave men with drinking. The rest of the ticket of leave men who were charged that year were either self

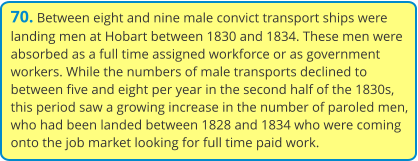

employed, like Thomas Tucker a bricklayer and Richard Barkley a carrier or employed on daily or weekly hire, or between jobs. Particular employers

seemed very averse to drinking and even charged two of their free workers. The Rev. Bedford charged his free labourer with drinking on a Sunday, which

attracted a 5/- fine as did farmer William Parramore, whose free man was also fined.

13

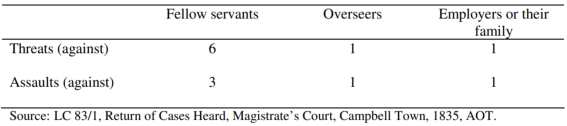

Table 9.1: Distribution of male “drunk and disorderly” charges in magistrates’ bench book for Campbell Town Police Dis-

trict, 1835.

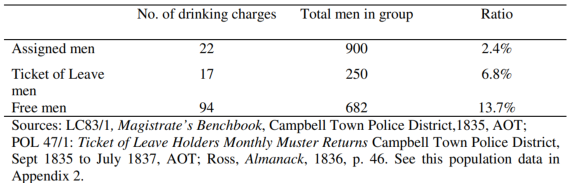

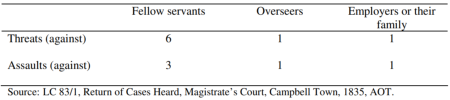

The 94 free men, who were charged before the courts were mostly emancipists. But even this group, who were apprehended in Ross or Campbell Town, generated on average fewer than two charges per week. Despite the public perception that drunkenness was one of the key barriers to reforming convicts, its visibility in the villages was low in this district, even amongst the two groups of convicts, the emancipists and ticket of leave men, who were legally permitted to drink in inns. As well as the low numbers of arrests for drunkenness, very few men were arrested more than once. Only three emancipists were charged three times during the year: William Fellows of Campbell Town; Patrick Moore, a saddler from Campbell Town; and John Schofield. The only person to be charged four times was a shearer and splitter from Sydney, William Davis. Several factors helped reduce public drunkenness in the rural villages. The convict police patrolled the streets regularly at night and local shopkeepers and others were likely to report incidents of disorderly behavior during the day. As well, fines of five shillings were significant for working men, some of whom only earned around ₤2 per month. These fines increased with subsequent offences to ten shillings and more. This does not mean that there wasn’t a pervasive drinking culture amongst the working men of the district, but suggests that most working men who drank, engaged in moderate drinking with a few occasional binges. Most serious drinking was likely to be done at home or in sly grog huts or in other locations out of sight, rather than in local public houses. Liquor was easy to obtain in the villages. A number of local men supplied the assigned village convicts and those on the nearby farms. Job Padfield, a ticket- ofleave man, was charged with trafficking clothes and liquor to several assigned men, working for John Mcleod, a farmer and trader on the outskirts of Campbell Town. 14 Charlie Blands, a free man, supplied liquor legally to Pat Kearney, one of McLeod’s ticket-of-leave men, but illegally in the same transaction to Charles Bonnick, an assigned man. 15 Isaac Wheatly, one of George Stewart’s assigned men, was caught trafficking liquor to other assigned men on the neighboring farm. 16 The above examples suggest that working men themselves didn’t bother making fine distinctions about who could buy or sell liquor. They simply used local supply networks to obtain it when they wanted it. Mostly, they were only caught if an assigned man was discovered very drunk or if someone was reported missing. While it is probable that some convicts who worked in the village inns made liquor available to others in the yards or tap rooms, only two inn workers were charged with this offence. James Johnson, a ticket-of-leave man who worked for publican Gavin Hogg, was charged with trafficking with one of the prisoners in the Campbell Town foot gang, probably in liquor- but this was not specified. Johnson apologized to the magistrate and had his ticket of leave suspended for three days. 17 It is likely that convict men who worked at inns, had moderate access to liquor for themselves and may have found it easier to traffick in small ways without being caught in the bustle of work in the large public houses. The truth about assigned convicts’ experiences on farms was far more complex than simple bench book statistics allow, especially if drinking was involved as the case at G. C. Clark’s farm revealed. Drinking could encompass betrayal, agency and opportunism in ways that reveal the complex reciprocities that groups of convict men negotiated with each other. Nine months of significant drinking amongst some of the assigned and ticket of leave men unraveled late one Sunday night, when several assigned kitchen staff went to Mr Purbrick, the head overseer and told him that three men had been missing since two o’clock that afternoon. They had gone over to Dixon’s farm to drink with one of his assigned men, John Markham who ran a sly grog shop. William Riley, an assigned shoemaker was central to the relationships that developed round drinking on the farm. Riley shared a hut with Whiting the gardener, where he cooked separately and worked at his trade during the day. As well as these privileges he made shoes in his own time to sell for cash. Like the eight ticket of leave men in Clark’s employ, Riley spread the cash round by getting several of the assigned men to do odd jobs for him, but two especially ran regular errands for him over to Markham’s hut to buy rum. Tutton and Simpson were paid in cash and rum for this, probably not only by Riley but also by two other ticket of leave men, John Cornelius and Will Travers who were also regular customers of Markham. Being out after hours was a much more significant breach of convict regulations than drinking and overseer Purbrick armed himself and set out through the bush to Markham’s to track down the missing men. He met Travers and Ward an assigned servant, walking home drunk along the fence line. They ignored his threat to shoot them if they didn’t stop, abused him and carried on home, informing him they could go where they liked. Purbrick and Dowling, the assistant overseer, found the third man Riley, back in his hut eating supper after midnight. The overseer reported all three men the next morning. The incident revealed some of the complex social relationships typical of many large farms. A small group of “yard” workers had privileges and more contact with the owner’s family than had the farm labourers. The kitchen staff, gardeners and craftsmen like Riley who had only been several months in the colony, were in this group and had their own accommodation closer to the main house, access to food privileges and easier jobs. The waged ticket of leave workers also had status, cash, good rations and their separate quarters. By comparison the convict farm labourers housed in the barracks did the worst work in all weathers, but some members of this group like Tutton and Simpson found it advantageous to align themselves with individual ticket of leave men or yard workers to pick up cash and other perks by being useful to them. In addition, Tutton was one of those convicts found on many farms who eavesdropped and collected information that could be handy to him and used it as collateral to help himself. When implicated in the drinking he acted as a witness against Riley and told the magistrate that Riley had also been supplying drink to two of the Clarks’ female servants, information that he had obtained from one of them when he found her drunk and made her tell him where she obtained the grog. Tutton also hid under the window of Riley’s hut that Sunday night and heard the argument Riley had with the gardener, whom he thought had reported him missing. Tutton discovered that the informers were several of the kitchen staff whose loyalties were more aligned with the overseer than with the shoemaker, whose activities appeared to be upsetting the balance of power amongst the different groups of workers. Riley well understood the check that other yard staff had on maintaining the status quo and retaining their privileges and complained that “there were four Bloody b---gg--s in the yard, if they were out of the way, we could do as we liked.” 18 The incident revealed significant absences too. Two bottles of rum shared between a dozen or so people every couple of weekends was hardly a drinking spree. It also appeared that the majority of the convicts were not centrally involved in the drinking circle, although they knew about it as word had got around that drink was on its way that Sunday afternoon. 19 None of the other six ticket-of-leave men were implicated in buying rum from Markham and only two of the nine assigned female convicts had succumbed to Riley’s seductions by alcohol. G.C. Clark, giving evidence, claimed he knew nothing about the drinking on his farm until the incident. Indeed, free overseers may have played a more significant role than employers on some farms, in ignoring moderate drinking to maintain productivity and keep the workforce happy. But it was a risky strategy. Once any of the drinkers got drunk, abusive or started relationships with the female convicts, it was likely that employers would soon find out. Overseers Purbrick and Dowling covered their backs well in this incident, helped by warnings from the loyal kitchen staff. While the drinking culture fueled complex layers of assertiveness, conviviality, betrayal and affiliations amongst convicts and free men, it could also be used by convicts to wring a profit out of supplying a prohibited item. Markham was an old colonial hand who had arrived twelve years earlier on the Malabar and saw the opportunities that his circumstances offered him with his own hut on the high road, the nearest public house four miles away, and up to twenty waged ticket of leave men on the surrounding farms who were entitled to purchase liquor. 20 Once the ticket-of-leave men brought drink onto the farms it was inevitable that some of the assigned men with cash would want it too. Markham was also well located to supply rum to the local shepherds who were selling grog to ganged absconders whom they were hiding in remote huts in the scrub at the back of farms. They too could make money by paying Markham five shillings a bottle for rum and selling it at a profit. But where did he get his supplies of rum? Although there is some general evidence that some convicts constructed stills in the bush to produce rough alcohol, Markham’s product seemed of much better quality than that. 21 Getting hold of the raw materials may have been more trouble than locating a regular supply of the finished product. Besides, the ticket-of-leave men were unlikely to pay a premium price for a poor product if they could buy the real thing four miles down the road at the Wool Pack Inn. With convicts assigned to a local distillery further down the Isis valley, it is possible that Markham got his supplies from there or else from Ross, perhaps dropped off by the same carters who carried it to market, or others who moved stolen goods around the district along with their legal loads. 22 Sly grog shops were located all over the district and most often on the roads to catch the passing traffic. Its probable that both free and convict carters supplied this trade by arrangement and quite regularly. 23 The drinking episode on Clark’s farm also offers some further insights into the extent of the cash economy which prevailed in convict ranks. Assigned men had even better opportunities of participating in the convict cash economy than their ganged colleagues. Many made or traded and sold items to their fellows: shoes, clothing, hats, liquor and services. Many were paid cash wages or bonuses by masters, or earned wages as ticket of leave workers. Some stolen and fenced goods were also traded. A fourteen year old prisoner, John Wood, revealed part of the lively trading culture that ticket-of-leave workers and assigned men engaged in on farms when he was incarcerated in the Campbell Town jail. Two assigned men supplied the local charcoal burners with meat from their master’s flock and a ticket-of-leave worker acted as a fence and did a good trade in second hand clothes. Wood claimed that his jacket had been stolen and resold. 24 Historians have underestimated the amount of cash that many convicts held. The Markham case is a good illustration. Markham sold rum at five shillings a bottle to local convicts, and some assigned shoemakers like Riley made enough cash from their private sales to buy a couple of bottles every few weeks. The ticket-of leave workers were paid around three to four shillings a day and in turn were likely to circulate their wages by drinking, gambling and buying services such as laundry work from their assigned work mates. 25 Other local employers gave evidence that their assigned men had cash either through wages or trading. In Campbell Town, store keeper George Emmett paid wages to some of his assigned servants and even increased them for higher duties. 26 In Campbell Town, James Thompson a neighboring shopkeeper told the magistrate that one of his assigned men, who appeared to have business dealings in Hobart, threw down bank notes on the table and taunted Thompson that he made more money than his master did. 27 But most assigned men had cash because their employers paid them a wage. This was widespread throughout the assignment period. Peter Murdoch told the Molesworth Committee that between 1831 and 1837 he employed ten to twelve assigned men and a free overseer on his dairy farm and four to five assigned men and a free overseer on his sheep run. In addition to their superior rations, clothes and accommodation, Murdoch paid his assigned dairymen eight shillings a week (₤20.8.0 per year). He was not specific about his shepherds’ wages, but it is likely they were paid about half of the skilled dairymen’s wages. By comparison, the free overseers’ wages rose from ₤40 to ₤100 per year during this period. Murdoch’s rationale for the payment of wages was strictly commercial. The dairymen were skilled workers who produced between 250 and 300 pounds of butter weekly, a job that required minute attention from the men and longer hours than most agricultural workers. These wages were in fact two thirds of the rate for free men. Murdoch paid his free farm workers ten to twelve shillings a week plus rations, but only employed them for short contract periods as they liked to go off to Hobart every month or so on a spree and spend their wages on liquor and women. 28 The committee questioned Murdoch further about this and they quoted Governor Arthur’s dispatch of 8 February 1833, in which Arthur asserted that he had forbidden the practice of cash wages and that this prohibition was observed. Murdoch claimed that both he and other settlers still paid their servants cash wages and gave them additional rations, but this varied from settler to settler. Once Murdoch was directly asked by Arthur whether he paid wages and he replied that he did and was told by Arthur that his assigned servants would be removed. On going to Hobart the next day to try and sort out this situation he was told by “an officer of some rank” not to worry about it, as he had been similarly threatened but he assured Murdoch “I make myself perfectly easy on the subject, because I know Colonel Arthur’s own servants are aid and we shall hear no more about it.” And so it was. 29 Murdoch’s evidence supported the view that the very structure of the farm labour force during the assignment period produced a farm hierarchy of workers with access to cash. A farm with ten assigned convict farm hands each paid ₤10 per annum, four freed or ticket of leave men - each hired on average for three months at 12/- a week and an overseer paid ₤70 per annum could create a cash pool of up to ₤200 a year. Larger farms with 20 assigned men, several overseers and eight to ten ticket of leave men could generate even more cash that could be circulated and redistributed amongst the farm’s total workforce. Cash was not likely to be evenly distributed amongst convicts. Clever traders, men with marketable skills and those willing to work hard and save for a purpose were likely to control more cash than the less skilled or motivated who drank or gambled it away. Assigned convicts’ access to cash has not been emphasized by many historians, but it was a powerful symbol of their control over their own lives, and a demonstration of the Convict Department’s inability to render convicts economically powerless. On some private work sites at least, convicts established their own hierarchies of control of significant resources such as cash and alcohol and redistributed them by supplying market needs within their own reach. Overseers, employers and even the convict administration turned aside and were complicit in or ignored most of these transactions. In doing so, farms, shops and factories came to increasingly resemble free worksites, where the power of negotiation, barter and payment was used far more frequently than Convict Department officials cared to acknowledge. While many assigned men empowered themselves through private business transactions, used cash and alcohol, received wages, and moved around the neighboring farms in their leisure hours, their main task remained to labour for their private employer in the place of free workers. More than 95% of assigned men worked on farms in the Campbell Town district. 30 In 1835 they numbered around 900 men. 31 Their work varied greatly according to the type of farm that employed them and the efficiency of their employer. Wool production required fewer farm workers and lighter work shepherding the sheep. 32 Shepherds drew lighter rations and lived in huts on the outskirts of the farm with less work and more autonomy than many other farm workers. They were generally in charge of 400 to 500 sheep which they walked through the bush and grasslands during the day, sometimes covering up to 30 miles. Around 666,000 sheep were grazed in Van Diemen’s Land in the mid 1830s mostly for fleece, with fleece prices varying from 9 pence to 16 pence a pound in Hobart and reselling in London for 1/6 pence to 2 shillings a pound. Wool was the largest export earner and in 1833 the colony earned ₤100,000 for its wool exports. 33 While most historians see colonial agriculture in terms of the growth of the wool industry, it can be forgotten that mixed farming employed more men than grazing due to its high labour intensity in an era when all farm work was done by hand. Up to twenty men could be employed all year at hard physical labour on mixed farms. Efficient farmers were encouraged to introduce mixed farming to make profits from the high prices the government paid for grain and meat to feed its convict labour force. In 1834 the government bought grain at ten shillings a bushel and meat at seven pence a pound. Any surplus was exported to New South Wales for the same purpose. This price bonanza varied throughout the 1830s as soil fertility declined. 34 In 1833 around 80,000 acres were under cultivation in Van Diemen’s Land: one third wheat, one third other grains and potatoes and one third English grasses and turnips for animal fodder. 35 These acreages did not increase much for the rest of the 1830s. High prices pushed efficient farmers into mixed farming for both fleece and foodstuffs, but many were inexperienced or poor managers and not all were able to enjoy the high profits. Dr James Ross provided inexperienced settlers with a complete guide to annual farming tasks in Van Diemen’s Land. The working year on a mixed farm revolved around the grain harvest. In April the ploughing, manuring and harrowing of the wheat fields started. The small acreages of wheat on each farm were constantly worked until planting was started in August. Bullocks had to be fed huge quantities of high quality rations of grains and boiled root vegetables during winter and spring to keep them at the plough. Sowing was staggered over three months so that the hand reapers could work through the crop from mid January to the end of March, as there was insufficient labour to reap a crop that ripened all at once. 36 In addition to planting wheat, feed crops like cape barley, rye, improved grasses and root vegetables needed to be produced on all wheat farms to feed the working bullocks, the main engines of the wheat crop. 37 Two planting and harvesting seasons existed for the winter and summer vegetables for men and beasts: potatoes, cabbages, turnips and others, which had to be harrowed and hoed throughout their growing periods. 38 May was root vegetable harvest time; September—the time to sow improved pastures; November—the shearing started; December was haymaking. 39 In addition, many farmers planted hedges, constructed fences and barns for their crops, fattened pigs and managed the constant stable and pen work for the bullocks, pigs and horses. 40 The mixed farmer, his sons and overseers had to carefully manage a workforce that varied throughout the year from between twenty to thirty men, to keep the farm producing and profitable. For the convict farm labourer this meant constant hard work in all weathers at the minimum from sun up to sun down. Assigned men were the primary full time work force of the farming Midlands, but one of the main difficulties settlers had to contend with was labour extraction. Assigned men understood they were used as forced labour, and even with the symbols of the lash and the chain gang constantly in front of them, some chose to resist through non-cooperation or pilfering. Others were unsuited to farm labour. They lacked the skills and experience or were physically or mentally less capable of adapting to this type of constant hard work. 41 However, most convict workers managed their working day by pacing their work, slowing down, ignoring overseers’ orders or going missing for short breaks. It is not surprising that the largest group of charges that employers laid against their assigned workers concerned the quality of their work and as Molesworth later noted in his report on transportation, these charges were overwhelmingly trivial in nature. 42 In the Campbell Town district in 1835 the bench book listed 58 charges for “gross disobedience”, another 29 for “insolence” and a further 22 for “neglect of orders”. 43 In some respects many of these charges could be seen as one of the main forms of protest identified by Atkinson—the withdrawal of labour. 44 In these cases the men mostly withdrew their labour either by working slowly, ignoring an order or sometimes refusing to work. Typical of such charges was one against Thomas Makin who failed to fetch the bullock chains or put the yokes away one afternoon after his employer’s son told him to do so. 45 William Huggins took one and a half days to bring 400 sheep in for shearing when his overseer estimated it was a three hour job. 46 One of the most common reasons for workers neglecting orders was that assigned workers were trying to enforce time limitations on their working hours. Many argued that the government hours of sunrise to sunset should apply on farms as well. They also demanded free time at weekends. John Macnamara refused to get up early and feed the pigs and bullocks in the morning and Thomas Witherstone curtly told his employer, who found the sheep in the turnips at 8am one morning that he should put fences round his crops as it was not his job to mind the sheep night and day. 47 Even juveniles like Richard Karsell, the blacksmith’s assigned lad, put down his tools and took time off to have his dinner rather than first finish the iron wedges he was making. 48 To some extent these actions reveal the men’s confidence in understanding and attempting to enforce convict regulations in respect of their work. Others attempted to bargain for additional perks in exchange for the extra time they had to work. This did not work with inflexible employers. John Wayland failed to get the tea and tobacco he asked for from Captain Horton in exchange for doing kitchen duties on a Saturday morning and fetching water for the house. 49 Although James Samual got new trousers to replace his torn ones, his master still charged him with refusing to work until the trousers were supplied to him. 50 Assigned convicts continued to manage assignment through these levels of resistance just as earlier groups of convicts had prior to 1820. 51 In fact, the structure of assignment and its use for farm labour in Van Diemen’s Land, gave an advantage to convict workers. The farm workforce was rarely more than 20 convicts and there was a high degree of division of labour on these sites with workers scattered across the farm on individual jobs. For these reasons it was more profitable for farmers to manage their workers with positive incentives rather than coercion. 52 However, certain employers, as in the above examples, used the magistrates’ courts to coerce their workers, regardless of the fairness of a convict’s request. In effect magistrates adjudicated the protests of assigned men who were resisting aspects of the system of forced labour, but as agents of the State, magistrates overwhelmingly favored the employers. The vast majority of these cases were decided against the men and harsh punishments were sometimes imposed. Other employers and assigned men negotiated changes in conditions that suited both parties and avoided using the courts. In doing this, both workers and employers ignored the convict regulations and forged their own work contracts thus creating conditions similar to the free labour market. Less common, but more worrying to employers, were convict threats or actual use of violence. However if the Campbell Town bench book is typical of ones in other rural areas at this time, most threats and assaults took place against fellow servants rather than overseers or employers.Table 9.2: Charges brought against assigned men for assault or making threats, Campbell Town district, 1835.

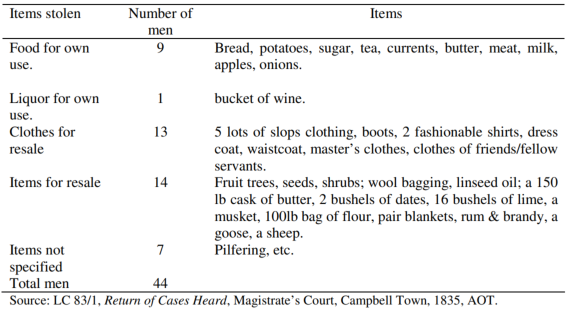

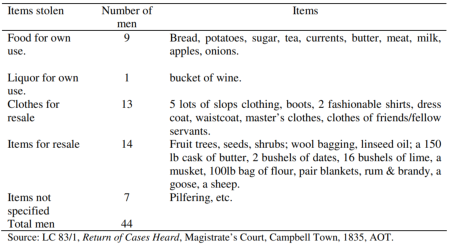

While most threats and assaults against fellow workers appear to have been about personal issues, in some cases, workers threatened others over poor work. Edward Harris threw hot water over a hut mate for causing them to be put on short rations and John Curry hit a ticket of leave worker who blamed him for losing the cows. 53 One overseer had to deal with contemptuous and threatening remarks from an assigned worker and another was threatened and hit by one who was drunk 54 David Murray, an employer whose many charges against his workers suggested he was inflexible and difficult to work for, charged Joseph Downing with threatening behavior because Downing protested vigorously when Murray accused him of stealing a pig. 55 While one farmer and his son were threatened with a hammer and a knife, some convicts objected to being threatened with whips or hit by their employers. 56 Assignment created a degree of physical conflict on farms between employers and their workers but in the Campbell Town district serious physical assault was rare, possibly because assigned men were subject to far less brutish coercion than the men in gangs but also because the consequences of such action would be severe. Atkinson identified two other types of common protests from convicts: the destruction of property and direct appeals to the magistrate. Neither of these was much used by assigned men in the Campbell Town district. Certainly there were no barn or rick burnings, which appeared to be more a strategy used by bushrangers. 57 Edward Gadsby, a free worker, was fined ₤2 for damaging a gig belonging to his employer; several assigned men allowed animals to die for want of care or others for permitting stock to trample crops. 58 A couple of carters were charged when goods being brought back from Launceston were damaged in transit or disappeared. 59 However, fewer than ten men were charged with these types of offences, some of which may have been acts of carelessness rather than malicious. As for stock theft, it was certainly a form of damage and farmers constantly complained about it. However, only eight men were charged with it during the year as it was extremely difficult to detect. 60 Few assigned men elected to charge their employer with a breach of the convict regulations. The exception to this however, was those employed on the Massey property. Massey senior was a military deserter who arrived in Sydney in 1804 as a convict. He and his sons ran two farms on the South Esk River near Ben Lomand and ill used their convicts by Massey’s own admission. As he put it: “I am obliged to use force with my servants. They will not obey my orders”. 61 Six of his assigned convicts complained to the magistrate during the course of 1835. John Knox complained of short rations, insufficient clothing and being struck by Massey and another worker complained of being hit on the head by Massey and being unable to work. Knox was sent off to a road party and the other returned to the Crown. 62 Another four of Massey’s men staged the only collective walk-off for the year, when they left the farm together and traveled down to the magistrate to complain about being denied the full ration of flour and one claimed he was not given proper bedding. 63 The sitting magistrates returned two to the Crown and sent the remaining two back to Massey, presumably as punishment, as they had previously tried to abscond. Despite the evidence against them, the right to convict labour was not withdrawn from the Massey’s despite the rules and regulations of the Convict Department. Although it is possible to identify all four types of convict protest from Atkinson’s paradigm in the records of the Campbell Town district courts, three of these were rarely used. Fewer than ten men were charged with damaging property, around thirteen with threatening or assaulting other convicts, overseers or masters, and only six appealed to the magistrates to redress their wrongs. Instead, the predominant type of protest was aimed at challenging the employers’ right to their enforced labour, through slow work, neglecting of orders, poor quality work and placing of limits on working hours. This can be described as an early form of industrial bargaining even though the records suggest that it was not entered into collectively but was more an action taken by individuals. However, Atkinson claimed that a form of collectivity was in the process of being formed by convicts and speculated that it was discussed and encouraged when convicts met in groups such as gangs or jails, where they shared information about their rights and established procedures they thought were fair, such as limiting their work or claiming the equivalent of wages by pilfering from employers. 64 Certainly Table 9.3 shows that around 10 local men were charged with stealing food or drink for their own use and another 20 or so with stealing clothes and other items from their employer to sell. In all about 20% of the assigned men of the Campbell Town district were charged over the course of the year with committing acts that can be seen as attempts to improve their living conditions. We can surmise an additional unknown number were never caught or at least never brought to court.Table 9.3: Charges brought against assigned men for theft or suspicion of felonies, Campbell Town district, 1835.

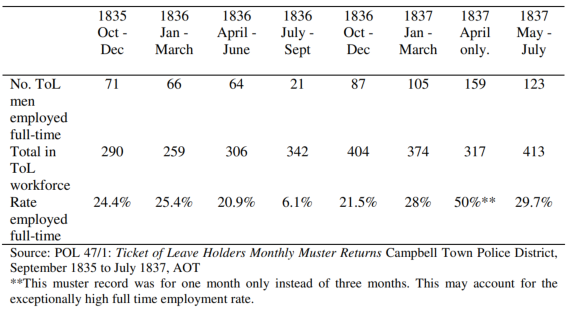

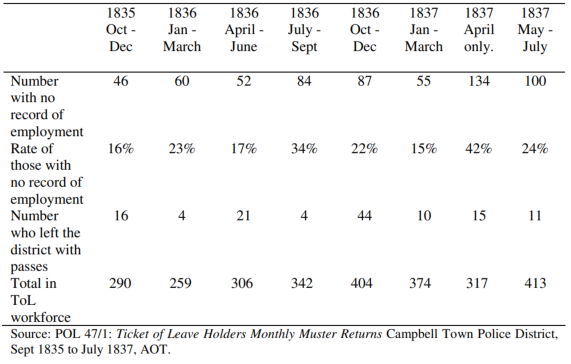

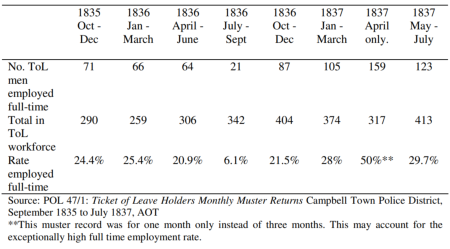

For the convict men who were the primary rural work force in the Campbell Town district, assignment was not a benign experience. Their work was hard and constant, overseen by private employers who were determined to make a good profit out of farming. Around 60% of the charges that employers brought against their men were related to their work including absconding or absenting themselves from work. 65 The consequences for breaching convict and other regulations were severe even though most of the charges were trivial. From the total of 324 charges brought against assigned men in 1835, the magistrates ordered 67 floggings, sentenced 22 to chain gangs and 47 to road parties for between two and twelve months duration. An additional 30 assigned men were sentenced to imprisonment either for a month or two in Launceston or for up to 18 months at the Port Arthur penal settlement. 66 Despite witnesses to the Molesworth committee suggesting that most private employers managed their convict workforce with cash incentives and extra rations, even so, in this district up to one third of the assigned men were charged with an offence during the year and around 50% of those charged received a severe punishment. 67 Around 18-20% of the total assigned male workforce received a severe punishment, often for lack of diligence or efficiency at work. As magistrates’ sentences were closely monitored by the Chief Police Magistrate in Hobart, it can be assumed that what happened in the Campbell Town district was also common in other rural districts in Van Diemen’s Land. These punishment rates show that labour was extracted from the assigned male workforce in rural areas by using a high rate of severe punishments to keep the men at their work. While district farmers used their assigned men as their permanent full-time workforce, they hired ticket-of-leave men to make up labour shortfalls at times of intense agricultural labour. Assigned men could not be fired at will and were valuable as they worked either for rations or for lower wages than other workers. By contrast, the surviving monthly muster records of ticket of leave convicts enable us to look at a number of aspects of their employment in the district. From 1835 to 1837 the number of ticket-of-leave men available for hire rose from around 300 to 400. At the same time, however, the number of assigned convicts steadily rose too, which made it increasingly difficult for ticket of leave men to obtain work. 68Figure 1: Ticket of leave male work patterns in the Campbell Town police district.

Source: POL 47/1: Ticket of Leave Holders Monthly Muster Returns Campbell Town Police District, Sept 1835 to July 1837, AOT. From October 1835 to July 1837 Figure 1 shows the relationship of the availability of full time and part time work in the district and the high proportion of men who apparently had little or no work at all. 69 Figure 1 demonstrates that by the mid to late 1830s the Campbell Town Police District was more than fully supplied with its general labour needs. 70 Moreover, the farmers managed their hiring needs by decreasing their numbers of full time ticket of leave men in quiet times and increasing their numbers of part time workers. Thus, where a man in a busy time may have got work for the entire three month quarter, in quarters of lower needs he might only be hired for one or two months. In all quarters there were always more men employed part time than full time. As Figure 1 shows, in some quarters, up to 50% of the ticket-of leave-work force only got part time work. As well, a large number of men, varying from between 15% to 34% of the total numbers of ticket-of-leave holders, were apparently without work—although it is likely that some in this group may have been hired weekly or even daily, and others may have already left the district without travel passes or been self employed. Although all ticket-of-leave holders were required to obtain travel passes from the local police office, if they wanted to move to another district for work, the muster sheets only noted that very small numbers of men had travel passes. Either the police did not record all the passes issued on the muster sheets or numbers of men just traveled on without obtaining them. Either way, this may have contributed to inflating the numbers of men who remained on the local muster sheets, ostensibly still in the district, but without any record of an employer or place of employment. In reality, it was difficult for even the local police office to keep track of at least 20% the mobile ticket of leave workforce that moved through the Campbell Town police district looking for work. This was especially so at times when insufficient employment was available for all seeking it.Table 9.4: Ticket-of-leave holders working full time, Campbell Town district, 1835-1837.

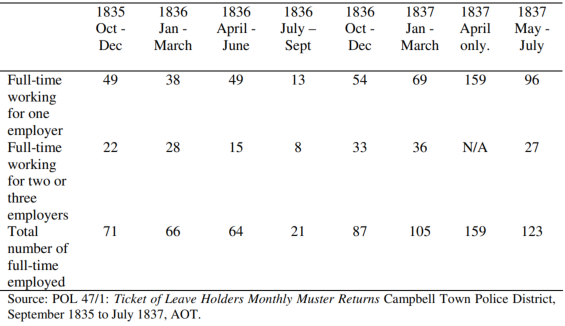

During the late 1830s, Table 9.4 demonstrates that the district only employed from 20% to 30% of ticket-of- leave men full time, depending of the seasonal labour requirements of farms. But even this group was split into those men who were employed full time by one employer for the three month period and longer, and those who worked throughout the three months but had to seek work with several different employers as Table 9.5 indicates.Table 9.5: Comparison of ticket of leave holders working full-time for a single employer and those working full-time for

several employers, Campbell Town district, 1835-1837.

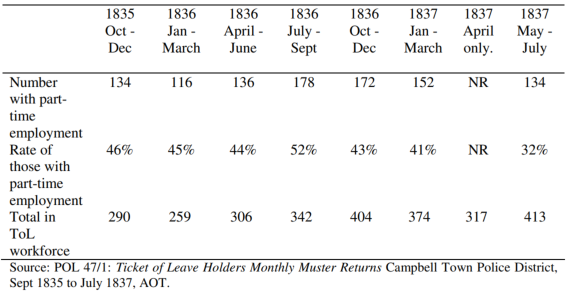

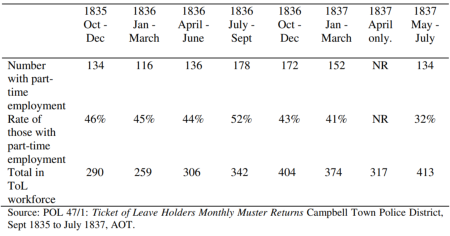

A specific group of large land holders showed a preference for employing the same ticket of leave men over longer periods of time. This group included G.C.Clark of Ellenthorpe farm, Mrs Abbott of Ashby, Dr T. Pearson of Douglas Park, James Makersey of Greenhill farm, Messrs J. A. Youl, J. Grant and W. Talbot all on the South Esk River and another dozen across the district. Some employers like Makersey and Clark employed up to eight ticket of leave men at a time for longer periods, demonstrating a commitment to this group of convict workers, who most likely were the best skilled and most hardworking of the ticket of leave holders. A smaller number of men, shown in Table 10.5, had to try harder to remain fully employed. These were the men who went from one employer to another and managed to remain fully employed for most of the time. Some of these were hired in rotation by a small group of farmers in one part of the district. For example, on the Isis River the Bayles, Dixon and O’Connell families frequently hired particular men in rotation during the busy wheat sowing, shearing and hay harvesting season from September to Christmas. During the same period the Parramores, Fosters and Harrisons did much the same thing on the Macquarie River near Ross. 71 Quite a few other ticket of leave men who managed to remain fully employed were constantly on the move looking for work nearby or further a field. As Table 9.6 demonstrates, however, the majority of ticket of leave workers in the district had a much grimmer time remaining employed. From 30% to 50% were recorded as partially employed. In effect this meant they worked only one or two months out of every three, yet very few were recorded leaving the district to look for work, until the last few months in 1837. 72 In part this was because the system was designed to prevent them from moving from district to district. Passes that restricted movement were an important means of keeping wage inflation at bay. It is possible, however, that some labourers preferred to take short term hires although it is not possible to determine from the records, whether it was the employer or the employee who was responsible negotiating the short term contracts.Table 9.6: Ticket-of-leave holders with part-time employment, Campbell Town district, 1835-1837.

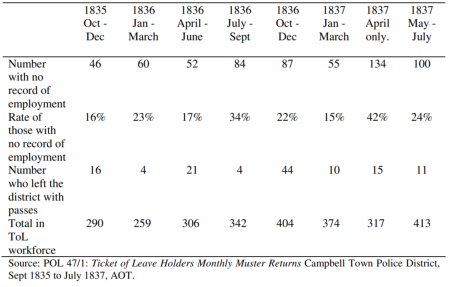

One employer claimed that he preferred to employ ticket of leave workers as he could retain them for longer periods than free workers, who liked to work for several months, then leave to go on a spree in Hobart. 73 This does not appear to be the preference of employers in the Campbell Town district though. Perhaps the very seasonal nature of mixed farming restricted local farm work to short contracts. The muster records of this period support this, suggesting that most ticket of leave farm workers were used as a supplementary labour force by local farmers, during times of high labour need, then discharged. Of course, some of these men may have obtained more work than was recorded on the muster lists by local police clerks. Additionally, employers, particularly those from remote farms, may not always have supplied accurate information to the police office about the constantly changing men in their casual workforce. The accuracy of the clerk’s entries varied substantially on the muster lists. If a police clerk had some personal knowledge of a man’s location it was sometimes added to the muster list as a note, but this appeared to depend very much on the inclination of the clerk. Some entries showed a run of the same employer over six months for one worker, but with several gaps. It was not possible to determine with accuracy if this literal recording of working four out of six months for one employer, indicated the worker was partially employed as recorded or if the clerk could not be bothered noting the name of the employer for all months. In these instances, I have taken a literal reading of the list and recorded the worker as partially employed. Similar problems exist when interpreting the remaining data in Table 10.7. Between 16% and 30% of the ticket of leave holders had no record of employment during the period the data was collected. As table 9.7 shows, very few of this group applied for passes to leave the district and find work elsewhere. This is especially so in the earlier months of these musters. For example, between January and March 1836, the local police recorded that they had no knowledge of the employer or location of 60 men, but only four of these had been granted passes to travel elsewhere. The data therefore suggests that a substantial number of ticket of leave men continued to live within the district, but without recorded employment and very likely were itinerant labourers working in the remoter areas or were able to live off the land.Table 9.7: Ticket-of-leave holders with no record of employment or place of residence, Campbell Town district, 1835-1837

(and numbers who left the district).

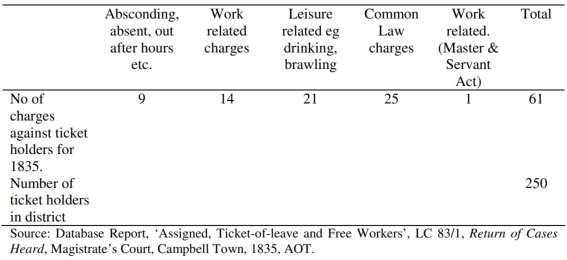

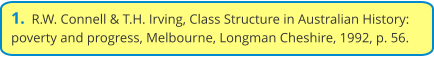

Some of them may have been men who were hired daily or weekly, and others may have found different sources of income including taking up clearing leases, felling timber, shingle making or charcoal burning in the tiers. There were many jobs such as fencing or harvesting on farms that an experienced rural worker could get for a week or two. Others may have found livings as tinkers or hawkers, buying and selling clothes or trafficking goods. A few would have serviced the pilfering and petty thieving of the district or become sheep stealers, to supplement whatever they made from casual wages. As finding work got harder, more ticket of leave men were charged with offences and had their ticket-of-leave suspended or worse. Up until December 1836, only four men had their tickets suspended and one was sentenced to a road party. In the seven months of records for 1837, this had increased to seven suspensions, four sentenced to a road party, four more sent to jail, and one with an arrest warrant out against him. 74 Despite this increase, the muster data records low conviction rates, even in times of decreasing employment options, although it is clear when we compare this data with the magistrates’ bench books, that the muster records may not accurately record the total number of these types of sentences handed down to ticket of leave holders. When the wheat harvest was in full swing, the two most popular destinations for ticket-of-leave holders were Norfolk Plains and Oatlands where work as reapers may have been available. 75 There was of course, a sufficient wheat crop in the Campbell Town district to keep six grain mills operating, but despite this, there appeared to be insufficient work for the 374 ticket-of leave-workers who were recorded in the district during the harvest months. Similar numbers left from May to July in 1837. 76 This relative mobility of ticket holders arriving and leaving each district monthly and the numbers of men with no location or employment recorded against their names on the lists, suggests that up to 20% of ticket holders were untraceable at any one time by convict officials. The monthly muster system only provided a semblance of control over the men’s whereabouts. Very few of the local ticket of leave men were able to establish their independence by working for themselves. The few who did were tradesmen or others and lived in Campbell Town or Ross. Their group included a harness maker, shoemakers, blacksmiths, carters and stonemasons. For a time one worked at St Pauls Plains and another at Avoca as shoemakers but this self sufficiency was often short lived. The musters rarely identified the men’s trades just noting “own hands”, signifying they worked for themselves. 77 Only a small number of these men appeared to continue to work for themselves for the whole twenty two months covered by the data. Others appeared to take some paid employment at times around the village and another group was only ever employed by the free tradesmen, shopkeepers, builders, publicans or emancipist tradesmen of the villages. Even those who worked for village employers rarely stayed with the same employer for the whole twenty two months, but changed employers several times in this short space of time. This entire group of village ticket-of-leave workers rarely exceeded 8% of the total number of men listed on the muster in any one month. 78 Around twelve such men worked regularly around Campbell Town, and another ten or so around Ross, during the period of the data. Contemporary witnesses, such as Alexander Maconochie thought the ticket-of-leave system was uncertain and unfair. He believed their good behavior was not taken into account sufficiently, instead they could be sent back to a road party for minor infringements of the severe restrictions they were under. Because their police records only recorded transgressions and did not list their good behavior, these records were biased against them and inadequate to judge their fitness for indulgences or punishments. 79 Although many thought the ticket holders behaved well and were better workers than assigned men or those with conditional pardons, one witness to the Molesworth committee had his doubts and argued that “I see people, when they are well off and comfortable, and getting good wages, behaving very well, and when they get into the opposite state they are very apt to relapse”. 80 Certainly some of the previous tables suggest that quite a number of ticket holders in the Midlands were out of work at least some of the time but did they go back to their old ways to make ends meet? Table 9.8 looks at the range of charges brought against ticket of leave holders in 1835, when 61 (24%) of them came before the magistrates.Table 9.8: Charges against ticket-of leave holders, Campbell Town district, 1835.

Ticket of leave holders could still be charged with being absent from duty, out after hours, failing to attend muster or leaving the district without a pass. A number were also picked up on suspicion of being a run away. The largest number (25) were charged with falling back on theft and the disposal of stolen goods, common law offences for which many of them were first transported. Seventeen of these charges related to consorting, trafficking with prisoners, receiving stolen goods, robbery, theft, suspicion of a felony or sheep stealing. Although it would be reasonable to suspect that most of those charged with felony offences would be unemployed, this was not so. Eleven of the group was either self employed or working for an employer at the time they were charged. Three were working on farms, two working in pubs and the others were self-employed as a carter, a couple of bricklayers, a sawyer, a blacksmith and a tenant farmer. It appears that some ticket of leave men retained links with the black economy and found it handy to supplement their income illegally in this way. For those who were employers or self employed, one was charged with withholding wages and six who were tradesmen working for themselves, were charged with breach of contract for not finishing work they had contracted to do. Another 21 were charged with general disorderly behavior which was common amongst working class men at the time. Of this number, 17 were fined for being drunk and disorderly, although magistrates seemed to accept that they were entitled to drink in public houses as long as they behaved. Another three were charged with assaulting their wives and a few more with fighting. With the exception of the 17 felony charges which were committed by recidivists, their punishments were more in keeping in severity with those handed down to free men rather than convicts. They were mostly admonished, fined or sentenced to several days in the solitary cell. However Maconochie was correct in assuming that those on felony charges received more severe sentences. Eight of these men were sentenced to road parties and another three to prison. Several more were remanded to the Quarter Sessions. Although their conduct records would not have listed their good behavior, in a rural district their general character was likely to be well known to police and they would have had the opportunity of submitting written assurances of their good character from local worthies. The small number of men who committed felony offences should not detract from the achievement of the vast majority of the two hundred and fifty ticket holders who made the transition to freedom without any significant court appearances before the magistrates. As one contemporary noted: “amongst lower class men, free and bond freely associate with each other… The free lower class man doesn’t attach stigma to associating with a convict, only the respectable classes do”. 81 In fact the convicts had never left the working class as Alexander Harris, a migrant worker, recognized when describing his own responses to the convict population. He was happy to work with them and share merry evenings with them in bush huts over a drink, a song and a yarn and “if there were many things in these men which I could not approve, there was much more that I could not but admire. There was a sort of manly independence of disposition, which secured truthfulness and sincerity at least among themselves in the bush”. 82 He believed that migrants, corn stalks, bushmen and emancipists had become engrossed in the business of colonizing in rural areas, with bullocks, land, timber and stock being the glue that welded them together. 83 The experiences of work in colonial Australia, as this study of the Campbell Town police district has shown was not a simple division between the free and the unfree. Because the labour force in rural areas was a mixture of assigned convicts, ticket of leave holders, emancipists, colonially born and free migrants, the experience of shared work began to outweigh the divisions that ‘convictism’ may otherwise have put in place. What emerged by the mid 1830s in both colonies was a distinct colonial working class which was rapidly developing traditions which would blur the divisions between the free and unfree, responding to the demands of a largely free enterprise economy.

Australian Colonial History

© Meg Dillon 2008

Chapter 9

The Male Workforce: farm and vil-

lage labour – working for the Man.

In the past, historians have emphasized the power of the large land

owners who had access to cheap land and convict labour and would draw

on kinship networks, influence in London and informal local networks

with colonial officials.

1

By comparison, convicts seemed to have few

means at their disposal to combat the combined forces of State power

and local paternalism. The rule of terror sanctioned by the colonial

government in the form of flogging and increasingly brutal penal

discipline, seemed enough to force convicts to accede to the conditions of

their servitude. This view fails, however, to account for persistent convict

resistance to many work conditions imposed on them, especially after the

Bigge Report attempted to reposition convict labour by tying it to the

expansion of the wool industry in both New South Wales and Van

Diemen’s Land. By encouraging a class of small capitalists to invest in

pastoralism and providing a cheap supply of convict labour, the

government unwittingly fostered the conditions for a classic class

confrontation.

2

This was particularly as the government enforced a

contract with the land owners that not only required them to pay for the

convicts’ keep in exchange for their labour, but also required them to

strictly enforce a rigid system of supervision and offer only a limited

number of rewards to men and women who showed evidence of reform.

3

Here an economic imperative and a moral one came into conflict, and for

most large landowners the need for profit was likely to be the more

important of the two.

This chapter examines some of the compromises that grew out of this

inherent contradiction. It first seeks to explore the recreational culture

amongst male convicts and the way that many employers and their

assignees renegotiated the official prohibition of banning access to

alcohol. The chapter investigates the supply trail of illegal liquor that

circulated in the district and the cash economy that thrived around it. The

complexities of negotiating the daily round of village work and coping with

the demands of the agricultural seasons are also explored. While assigned

males formed the primary rural workforce in the Campbell Town district,

the use of the growing numbers of ticket of leave holders as a

supplementary workforce during periods of high labour is also examined.

This chapter will conclude by looking at the effects that their presence had

on farm labour relations.

Although not all convicts drank, for many assigned workers drinking had

cultural meaning. It marked the difference between work time and free

time and was often associated with a number of leisure activities which

were enjoyed collectively. It was accompanied by gambling, singing,

yarning, smoking and reading and was probably almost always present

when the men organized the popular pastimes of sparring, cock fighting

or dog baiting.

4

Some also used it to gain sexual favors from convict

women. These activities grew out of traditional working class culture

which was replicated in the colony although it was often restricted to

convict quarters, shepherds’ huts or other remote spots well away from

the employer’s house.

5

Such social activities were important in helping to

redefine the likes of assigned workers as something other than convicts.

For the men, free time on many farms marked a space into which neither

their employers nor the system should intrude.

6

Employers, who had managed farms in Britain, recognized a number of

benefits that moderate drinking traditionally provided the rural labourer.

Indeed the provision of alcohol was often recognized as an important

mechanism for creating a more harmonious work force and most masters

turned a blind eye to moderate drinking as long as it did not interfere with

the men’s work or cause fights.

7

Their convict workers were capable of

generating “an internal cultural world” that maintained social links within

their class traditions.

Although drinking was an important marker of class and by extension

convict culture, it was not frequently prosecuted. Table 10.1 shows that

assigned men had the lowest percentage (2.4%) of prosecutions for

drinking of any male group.

8

This does not necessarily indicate they did

not drink, but it does suggest that most assigned men, who drank, did so

moderately or did not attract the attention of their employer, or their

employer ignored this behavior. A slightly higher percentage of charges

(6.8%) were laid against ticket of leave men. Even so, fewer than one

convict from the private sector labour force was charged per week with

being drunk and disorderly.

Some of the assigned men were picked up by the police while drinking in

public on Saturday or Sunday. Dickenson’s pub at Ross was a strong

attraction for three of them. Charles Burdit confessed to the magistrate

that “I got the drink at Dickenson's. The girl brought me a pint of wine

which made me tipsy. They did not ask me who I was. It was after

church."

9

Thomas Bowles was also picked up on the street in Ross on a

Saturday afternoon.

10

Another was caught in the Christmas Day riot at

Dickenson’s and got 40 lashes.

11

All were assigned to farms close to Ross

and walked into the village in their own time and had the cash to purchase

drinks from the tap room of the public house. Likewise, drinking on the

farm was only a problem for five or six employers who charged their

assigned workers. As five of the drinking charges occurred in August it is

possible that some of the men received cash bonuses for the end of the

ploughing season and may have spent this on grog. Although this was the

only appearance for each of the assigned men before the magistrate for

the year, the sentences varied considerably from admonishment to 25

lashes or three months with a road party.

12

This suggests that those who

received the more severe sentences were unsatisfactory in other ways

which were not specified in the charge.

Again only five farmers charged their ticket of leave men with drinking.

The rest of the ticket of leave men who were charged that year were

either self employed, like Thomas Tucker a bricklayer and Richard Barkley

a carrier or employed on daily or weekly hire, or between jobs. Particular

employers seemed very averse to drinking and even charged two of their

free workers. The Rev. Bedford charged his free labourer with drinking on

a Sunday, which attracted a 5/- fine as did farmer William Parramore,

whose free man was also fined.

13

Table 9.1: Distribution of male “drunk and disorderly”

charges in magistrates’ bench book for Campbell Town

Police District, 1835.